|

Best

film in 1975 for original story and overcoming difficult filming with

excellent direction from Steven

Spielberg. When the composer John Williams played the two main notes on the piano, Spielberg thought he was joking, and said: “That’s very funny, what’s the real score?”

Jaws

is one of the movie greats, released in 1975, following the success of Peter

Benchley's novel of the same name. It was the best film of the year

and a summer blockbuster, released just when the beaches were full of

swimmers. Wow!

It

is also one of the most important movies of all time, because of the way

it influenced other directors and producers making films. Forty-five years

ago, the summer blockbuster was born.

Forty-five

(45) years later and it is still as enjoyable as the day it was released -

except that the animatronic

shark lets the cast and filming down as to realism. But hey, this was

1975. In June nineteen seventy-five this was as good as it gets. One of

the best things about the original was the distinctive and very

descriptive sound track.

There

still is no shark film to touch it, because the mix of story, cast and

direction (apart from Bruce) was just right.

TIME

- JAWS 40th ANNIVERSARY JULY 2020

Forty years ago Saturday saw the release of

Jaws, an adaptation of a beach-read made by a promising but relatively untested young director, Steven Spielberg. Forty years later, Jaws‘ impact can be felt across moviegoing.

The shark tale is perhaps most notable for its box-office success; Jaws became the top-grossing film of all time after its release (and did so more quickly than had its predecessors, with a marketing plan based on blanket advertising rather than a slow rollout). Jaws, with its technical mastery and ability to manipulate the audience into fearing something that for so much of the film’s running time they could not see, was a movie that demanded to be seen as soon as one could, just like later blockbusters including Star Wars (which, two years after Jaws, replaced it at the top of the all-time box office list).

Jaws established Spielberg as an economic force, which means more than one might think; he has proven, in the intervening years, to know exactly what the public wants, from ultimately vanquishable scares (Jurassic Park) to charismatic heroes (Indiana Jones) to sweet sentiment (E.T.). Jaws gave him the capital to do whatever he wanted; his next film was the more adventurous Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Directors less technically adept than Spielberg, though, took from Jaws the lesson that bigger is better. This summer’s biggest movies so far (Furious 7, Avengers: Age of Ultron and Jurassic World) are all heavy on chases, fights and/or explosions. Jaws had a mechanical shark, yes, but its impact as the first true blockbuster in Hollywood history stems not from the suspense but from the few scenes when the mechanical shark attacks.

BEST

SUMMER BLOCKBUSTERS - EVER

1. Jaws

2. Star Wars

3. Jurassic Park

4. The Dark Knight

5. Raiders of the Lost Ark

6. E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial

7. Forrest Gump

8. Ghostbusters

9. Animal House

10. Terminator 2: Judgment Day

11. Top Gun

12. The Sixth Sense

13. The Lion King

14. Superman II

15. Back to the Future

16. The Avengers

17. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2

18. Grease

19.

Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl

20. Toy Story 3

21. Independence Day

22. Gladiator

23. Saving Private Ryan

24. Spider-Man

25. Inception

26. Shrek

27. There’s Something About Mary

28. Rambo: First Blood Part II

29. The Hangover

30. Bridesmaids

IB

TIMES JULY 2020

The 40th anniversary of the initial release of Jaws is marked on 1 June 1975, striking a fear of sharks into a whole generation to follow. It opened in cinemas across the US a few weeks later and would go on to become the highest grossing film of

that time.

40

FACTS ABOUT SPIELBERG'S GREAT WHITE SHARK MOVIE

1. The great white shark in the film was estimated to be around 25ft long. The biggest great white to have ever been caught in real life was around 20ft.

2. The film was based on the book by Peter Benchley. He based it on a series of shark attacks that took place off the coast of New Jersey in 1964 and a 4,500lb shark caught in 1964 off the coast of Montauk.

3. Other titles for the bestseller included The Silence of the Deep, Leviathan Rising, and The Jaws of Death.

4. Despite widespread belief, stunt woman and actress Susan Backlinie did not break her ribs or hip while filming the opening scene, meaning her screams of terror were real. However, Spielberg did not warn her when she would be 'attacked', so her reactions were more genuine.

5. Richard Dreyfuss was not Spielberg's first choice for the role of Matt Hooper – Jeff Bridges, Timothy Bottoms and Jon Voight were all approached first.

6. The iconic poster for Jaws was designed by artist Roger Kastel for Benchley's book.

7. In the book, Hooper dies and Quint is killed by drowning – he is dragged underwater after harpooning jaws. In the film, Hooper lives and Quint is eaten alive feet-first.

8. On set, Robert Shaw (Quint) and Dreyfuss (Hooper) did not like each other, providing some of the tension between the pair.

9. Five people are killed by jaws in the film – Chrissie Watkins, Alex Kinter, Ben Gardner, a man in the estuary and Quint. A dog also died.

10. Spielberg initially did not like the music saying it was too simple. He changed his mind later.

11. Credited with being the first summer "blockbuster" after over 67 million people in the US went to see it.

12. Jaws made over $7m in its opening weekend – not far off the $9m production budget.

13. Three mechanical sharks were used in the filming with each having specialised functions. They were nicknamed "Bruce" after Spielberg's lawyer.

14. The first shark killed in the film was a real shark killed in Florida.

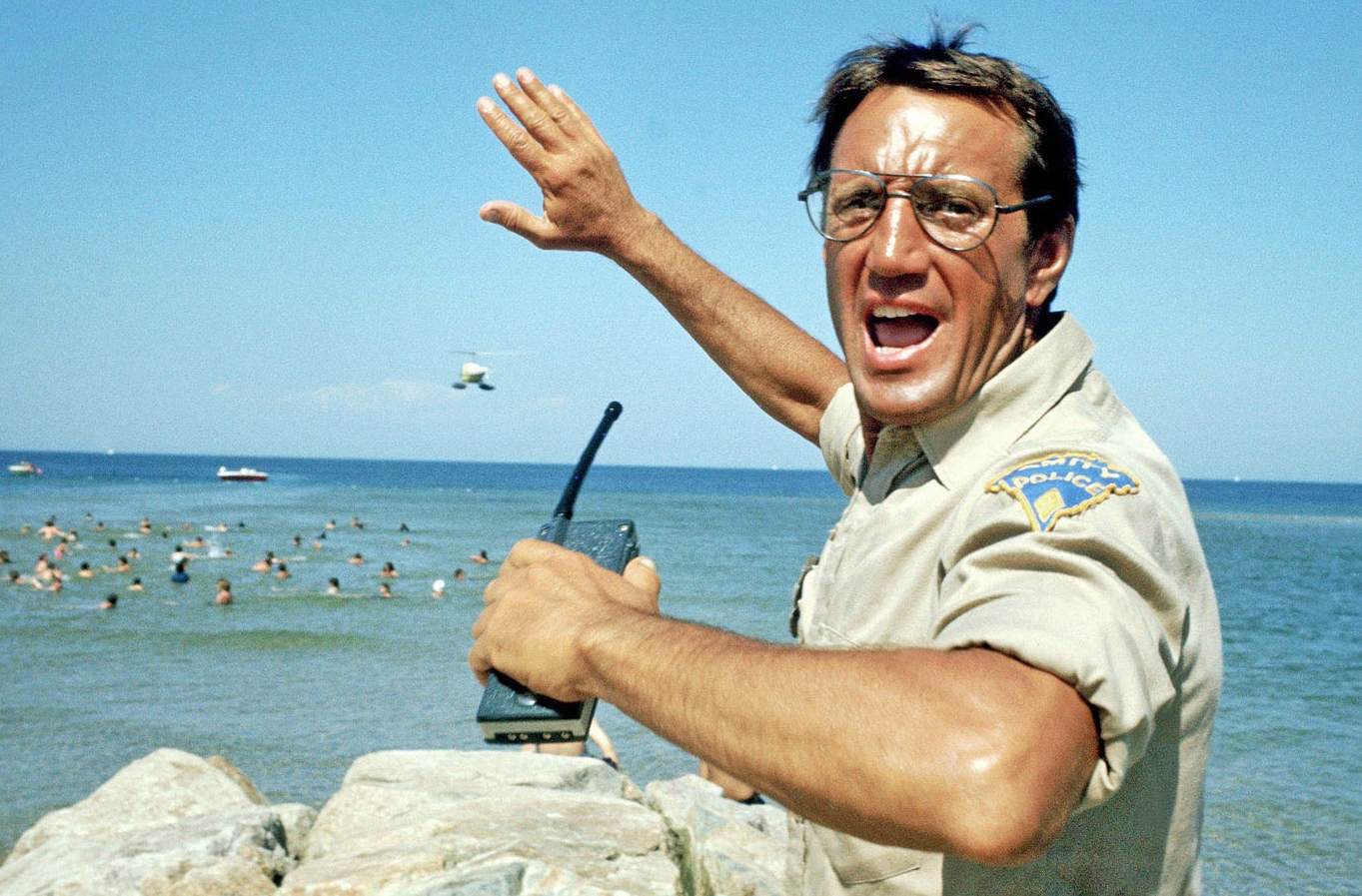

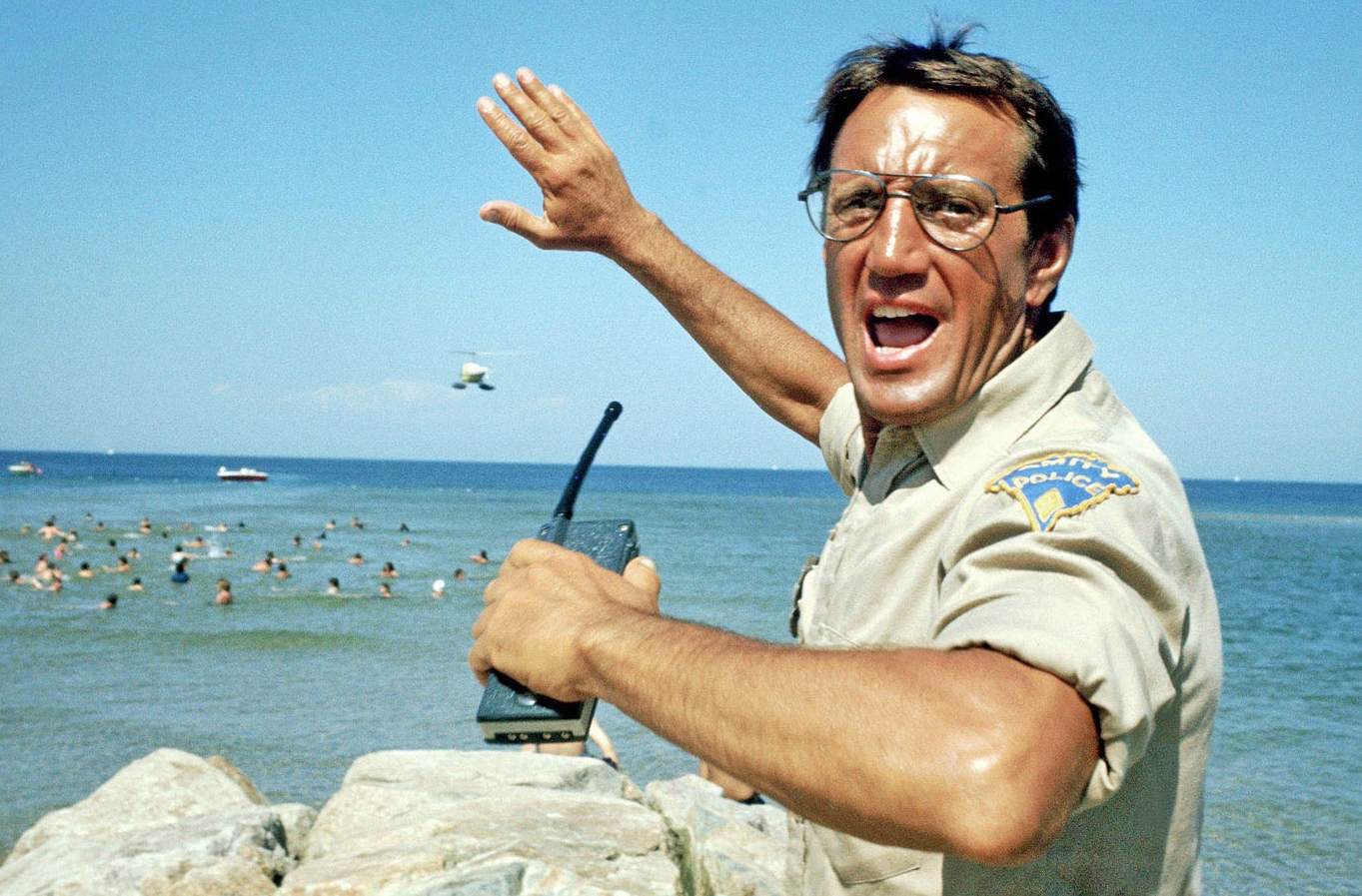

15. The film's most famous line – "We're gonna need a bigger boat" – was improvised by Roy Schnieder.

16. When the first victim's hand is found in the sand, Spielberg said the fake arm they had bought looked too fake, so they buried a crew member in the sand with her arm sticking out.

17. Fidel Castro enjoyed Jaws and considered a wonderful piece of Marxist propaganda. He said he thought the shark was attacking American culture and capitalism.

18. Brody's dog in the film was Spielberg's dog in real life – Elma.

19. Spielberg was not the original choice for director. The first choice was scrapped because they did not know the difference between a whale and a shark.

20. The first mechanical shark was not tested in water before production started and when it was placed in the ocean it sank to the floor.

21. Charlton Heston wanted to play the role of Brody and when Spielberg turned him down, he vowed never to work with the director.

22. Jaws is credited with vilifying sharks, creating a perception of them being dangerous killers.

23. Shark expert George Burgess told National Geographic that the film initiated a huge decline in US shark populations with thousands setting out to catch them as trophies.

24. The books' author Benchley went on to become a conservationist and became filled with regret for having written Jaws. He said, "knowing what I know now, I could never write that book today".

25. On average, five people are killed by sharks every year, with around 75 attacks in total globally.

26. More than 100 million sharks are killed by humans every year.

27. In the 1970s and 1980s, Great White Shark populations in the northwest Atlantic had plummeted by around 70% since 1961 levels.

28. In 1997, a US federal law was introduced banning the hunting of great white sharks.

29. In 2013, a South African fisherman became the first person to be prosecuted for hunting a great white – it had been illegal there since 1991.

30. Around a quarter of Jaws was filmed from water level to give the audience the perspective of treading water.

31. In reality, sharks do not like eating humans because we are too bony – we are not seen as being nutritious enough to be worth the effort.

32. Most shark attacks are the result of test bites – after an initial taste, they normally won't return, which is why most attacks are not fatal.

33. The great white was is thought to have been chosen to represent Jaws because it is the only species of shark that can stick its head above water to look for prey.

34. Popularised the film technique of the 'dolly zoom' filmmakers use to give the sensation of vertigo.

35. Jaws won three Oscars – Best Sound, Best Film Editing and Best Music, Original Dramatic Score. Spielberg won a Golden Globe as Best Director for it.

37. Jaws does not appear in a shot fully until an hour and 21 minutes into the film – which is just two hours long. This is because the mechanical shark rarely worked, not as a ploy to build tension.

38. Spielberg did not direct the final shot of the shark exploding – he had returned to Los Angeles to begin post production and left the scene to the second unit.

39. Benchley was not happy with the ending and was thrown off the set as a result. He said the explosion was unrealistic, to which Spielberg replied the audience would believe anything after two hours.

40. The chance of being killed by a shark is one in 3.7 million.

EW

- JEFF LABRECQUE AUGUST 3 2020

When I was growing up on the Jersey Shore, mere miles from the 1916 shark attacks that Peter Benchley used as inspiration for his best-selling novel,

Steven

Spielberg’s Jaws had a profound effect on my summers. Whenever I was alone in the water, I inevitably began to fear that I was being stalked by something beneath the surface. The panic would grow and grow — as John Williams’ daaa-dum music grew louder in my head — until I finally felt compelled to make a break for it. Swimming for my life, my flailing arms furiously pounded the water and my lungs felt about to burst because my face never turned to gulp more air. In my mind, the Great White from Jaws was inches behind me, his mouth wide open, about to turn me into lunch. I never dared slow down or look back until my entire body was out of the water… and safely back on the deck of the pool.

See, that was the thing about Jaws. The fear was so visceral — and irrational — that even a dip in a chlorinated swimming pool seemed like a risky proposition to a kid whose imagination was much deeper than the pool’s diving well.

It’s true that Jaws was the first summer blockbuster, a national event that consumed the culture for an entire sweltering season — and then some. The summer movie season had traditionally been a Hollywood dumping ground, but Jaws was a beast as soon as it opened on June 20, 1975, changing every element of the movie business forever. It was an immediate smash, winning 14 straight weekends at the box office, and broke most all the important box-office records. It helped that the movie was brilliant pure entertainment, but Universal marketed the movie in a bold new way. Before Jaws, most promising studio pictures opened gradually, first in major cities before branching out to the suburbs and more rural areas. That would allow word of mouth, and hopefully positive reviews, to pave the way for a long, profitable run in theaters. Instead, Universal exec Lew Wasserman adopted a technique that was typically reserved for stinkers: saturate the airwaves with massive TV advertising and open across the country simultaneously in order to bypass the critics. Jaws opened in more than 400 theaters, which was a lot at the time, and the reaction was immediate. Everybody was talking about Jaws. Everybody wanted to see what the fuss was about. Everybody then wanted to see it again. And again. And again.

As most fans know, the making of Jaws was a complete nightmare for 27-year-old Steven Spielberg. The script was nebulous, the clunky mechanical shark nicknamed Bruce wouldn’t work properly, and the budget ballooned from $3.5 million to about $10 million as the 55-day shoot in Martha’s Vineyard stretched to 159 days. “If any of us had any sense, we’d all bail out now,” said Richard Dreyfuss, during one of the first days that Bruce refused to cooperate. Spielberg woke up every day fearing — and perhaps occasionally hoping — that he would be fired from the project and his career would be over before it really got started. But it turned out that the shark’s chronic malfunctions were a blessing in disguise, forcing Spielberg to repackage the creature as a more Hitchcockian device that is seen less but felt more. Audiences don’t see the shark in the movie until the final act, when Roy Scheider’s Chief Brody backs away from chumming the sea and tells the salty

Melvillian captain played by Robert Shaw, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

What was supposed to be a historic bomb became the biggest movie of its time, but the film’s phenomenal success isn’t the only reason it tops our list of summer blockbusters. Before Jaws, the idea of a movie about a rogue shark terrorizing a small seafaring village was not taken seriously by the studios. This was the realm of Roger Corman’s B-movies, cheap schlock that was made in a hurry to play on the drive-ins in the sticks. Before Jaws, there were films and movies — and never the twain shall meet — but Jaws bridged the gap. The day after audiences watched Scheider blow up the shark, every studio started digging in their basement for their own summer blockbuster. Jaws opened the door for science-fiction odysseys, comic book heroes, and Disney theme-park rides to dominate the big screen, and Hollywood has never been the same since.

Jaws ultimately grossed more than twice the year’s second biggest hit (the Oscar-winning One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) and was nominated for four Academy Awards, including one for Best Picture. Beginning a trend, Spielberg was not nominated despite all the blood and sweat he had put into it. Nor was Shaw, whose portrayal of the grizzled shark-killer, Quint, is now considered one of the all-time great performances. For a movie about a killer shark, its most harrowing moment isn’t the pretty skinny-dipper being pulled under or the shark finally smiling for Brody, but Quint’s half-drunken story about the U.S.S. Indianapolis, the

World War II vessel that was torpedoed in 1945 and left to be preyed upon by sharks.

Here’s to swimming with bow-legged women. Jaws, oft-imitated but never equaled, the greatest summer blockbuster of them all.

Rank: 1

Release Date: June 20, 1975

Box Office: $260 million domestic ($7.0 million opening weekend), $470.7 million global;

$1.02 billion domestic in 2014 dollars, adjusted for inflation. (All numbers from Box Office Mojo.)

The Competition: There was no competition. Jaws swallowed the competition whole, including Nashville, which had been the No. 1 movie the week before. Who else had the misfortune of opening in the summer of 1975? The Apple Dumpling Gang with Bill Bixby and Tim Conway, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, The Other Side of the Mountain, Rollerball, and Woody Allen’s Love and Death.

What TIME said: “Like all the best thrillers — with which this movie is good enough to keep company — Jaws relies on both the immediacy of illusion and the safety it provides. The menace so cunningly created and enlarged comes close enough to have caused loud screams and small tremors of terror at pre-release screenings. Yet Jaws is vicarious, not vicious, a fantasy far more than an assault. It is a dread dream that weds the viewer’s own apprehensions with the survival of the heroes. It puts everyone in harm’s way and brings the audience back alive. And in Jaws, the only thing you have to fear is fear itself.”

Cultural Impact Then: People flocked to theaters in the summer of ’75 to see Jaws, but the movie had an adverse impact on beach attendance, with anecdotal reports that people were staying away from the water. The film was so effective that sharks — especially Great White sharks — were demonized, and nearly 40 years later, they remain feared and misunderstood based on the misconceptions presented in Jaws and its sequels. The enormous success of Jaws demanded a sequel, and Jaws II was quickly green-lit with Scheider starring. (Spielberg and Dreyfuss escaped the follow-up because they were busy making Close Encounters of the Third Kind.) Other studios quickly generated their own Jaws rip-offs, with

Orca, The Deep, Tentacles, and Piranha soon swimming into theaters.

John Williams’ chilling, immediately iconic score won him an Oscar and became the summer’s most repeated two notes. A new NBC sketch show that would become known as Saturday Night Live featured a recurring Land Shark who duped naive people into answering their door.

Most long-lasting, Jaws‘ success didn’t end at the box office, as the public was in a frenzy for movie-related T-shirts, posters, toys and lunchboxes. It paved the way for the kind of merchandizing that would explode two years later for Star Wars, which took the Jaws blockbuster blueprint to another level.

Cultural Staying Power: People are still terrified of sharks, so there’s that. And people still sit up straight when Williams’ score gets played. But the most important cultural impact of Jaws was the advent of the summer blockbuster. Hollywood wholeheartedly embraced huge event movies that became the centerpiece of their strategy. Some blame Jaws, and subsequently Star Wars, for the demise of the auteur-led Hollywood by replacing pseudo-artistic entertainment geared for adults with frivolous fodder for kids. Then there was Jaws II and Jaws 3-D, and The Empire Strikes Back and The Return of the Jedi. Studios suddenly demanded blockbusters that could be made into more blockbusters; i.e., franchises. That’s a lot to hang around the neck of one nearly perfect movie that many predicted would be a total disaster. Jaws didn’t kill Robert Altman, but perhaps it made making his brand of movies that much more difficult.

Steven Spielberg became the master of the summer blockbuster, as our list attests. Making Jaws gave him near-complete freedom to make any movie he wanted for the rest of his career, and he’s delivered on that promise time and time again, in movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T.,

Jurassic

Park, and Saving Private Ryan, to name but a few.

Jaws also influenced an entire generation of filmmakers who aspire to tell a big-budget, high-concept story as perfectly as Spielberg did — though many have wisely steered clear of filming on the water. His nightmare experience off the coast of Massachusetts has become legend, with multiple documentaries picking through the production headaches and the personality conflicts that plagued the shoot. Last year, two different scripts about the making of the movie were included on the annual Black List, which highlights the best unproduced screenplays in Hollywood. Jaws also gave us the annual Shark Week and Sharknado 2, so there’s no denying that it has become one of the most important movies of all time, for better and worse.

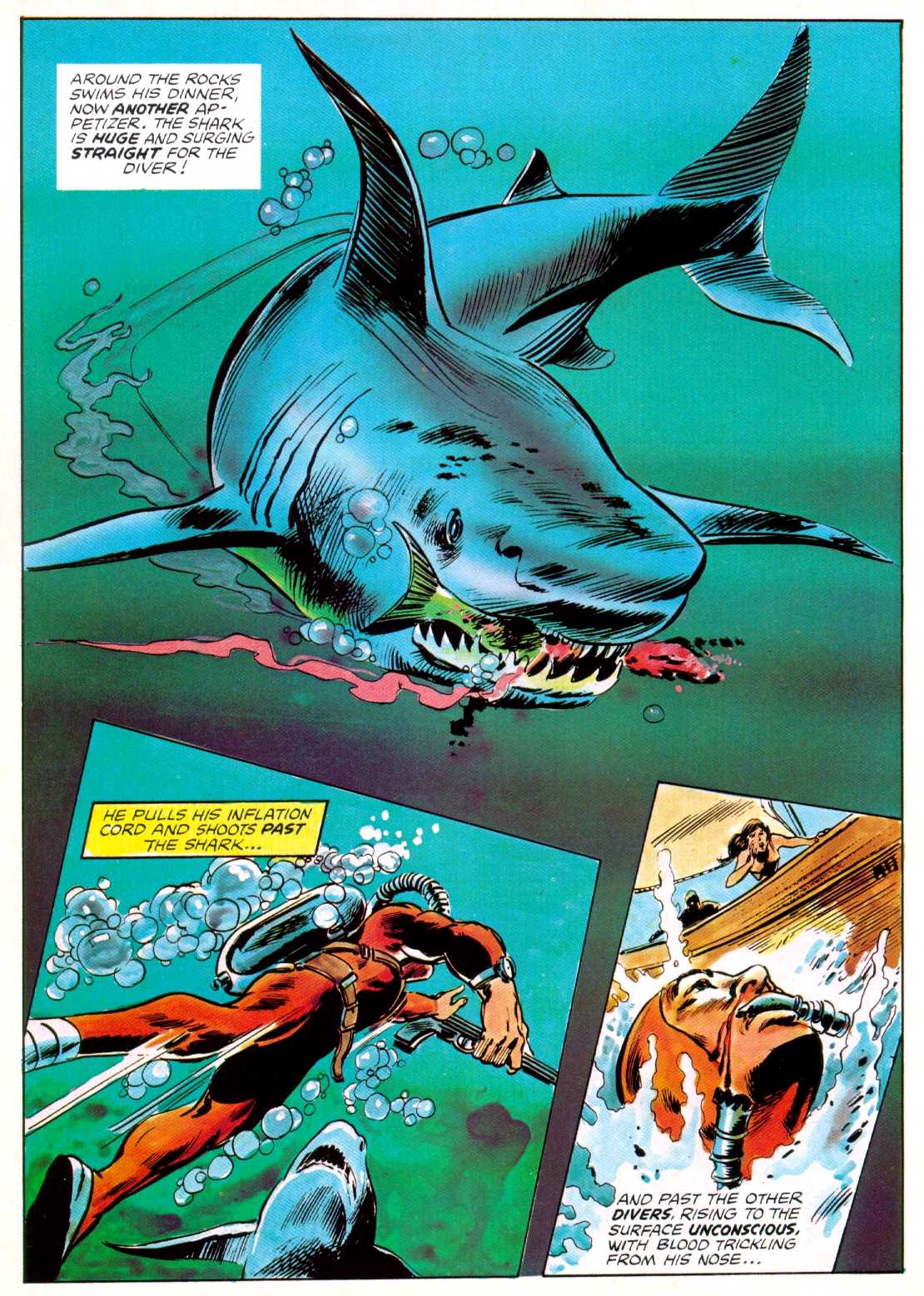

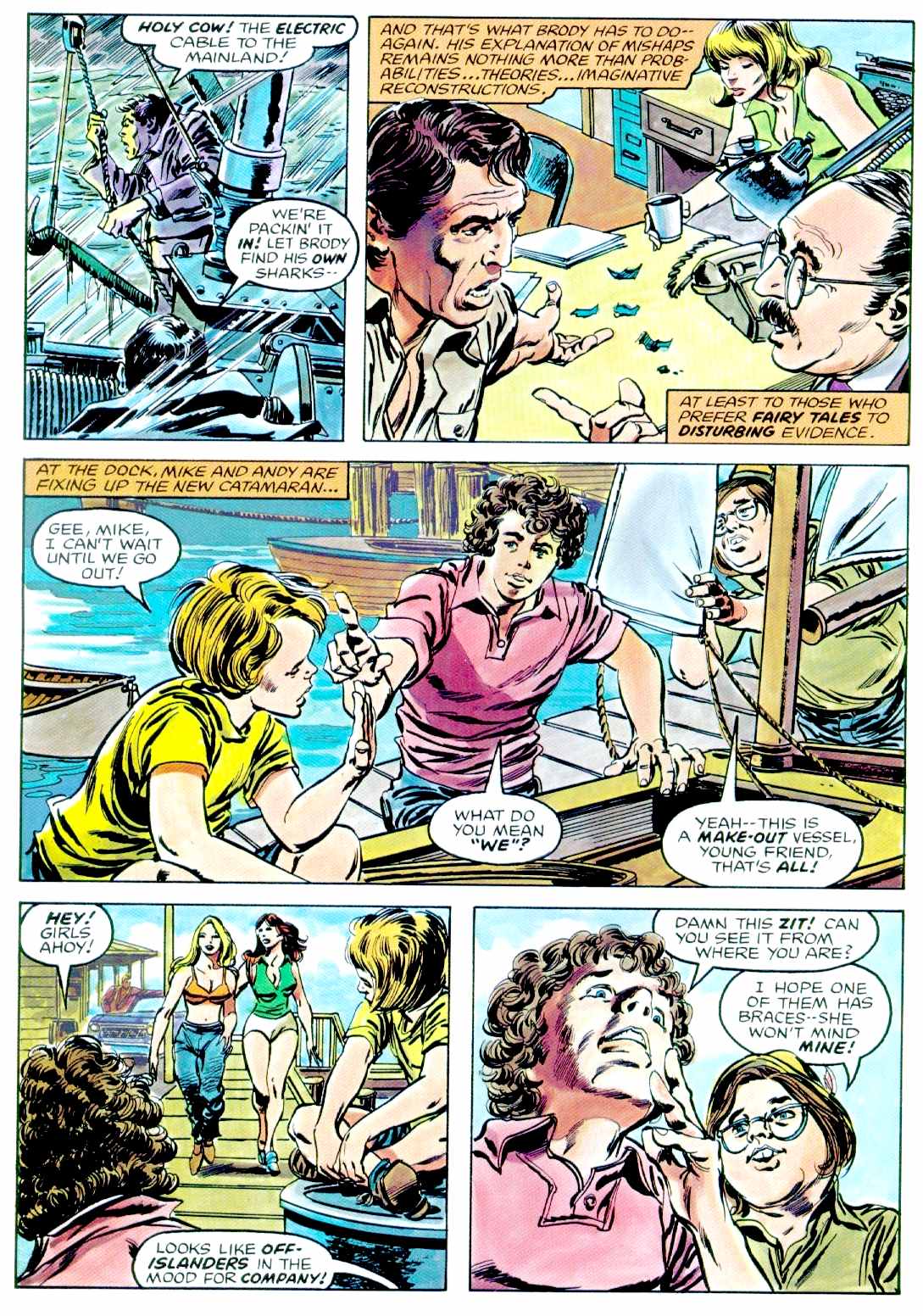

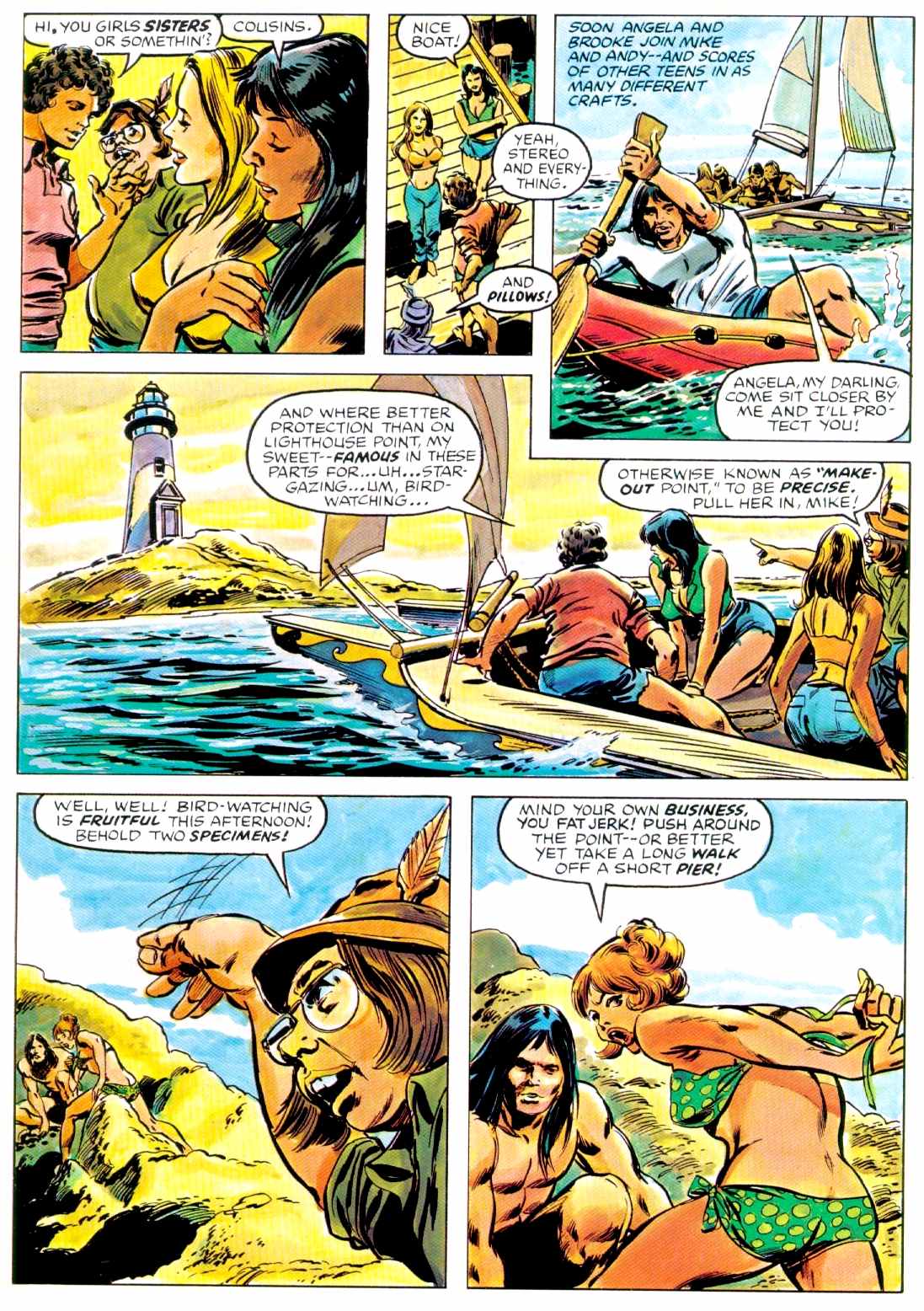

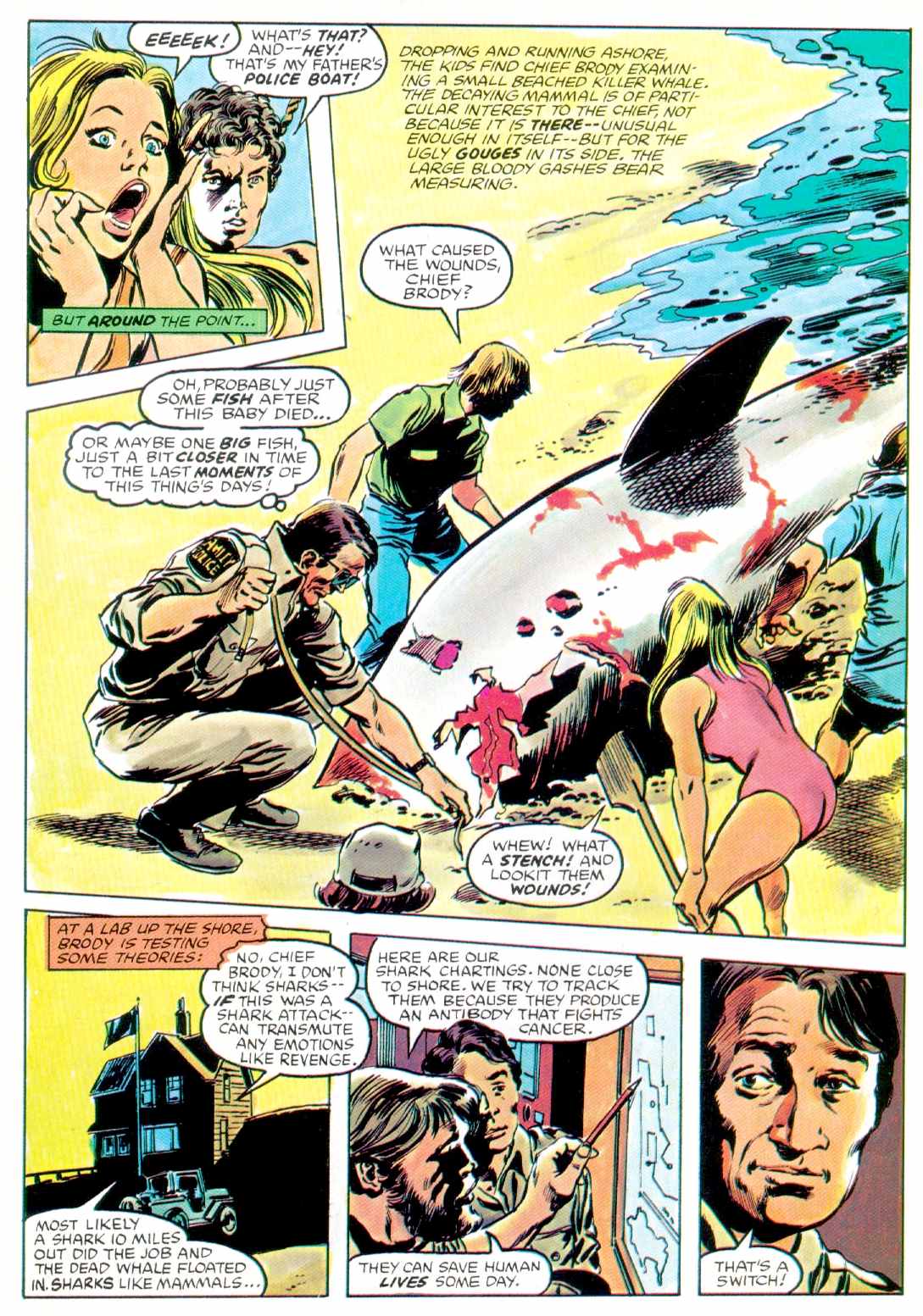

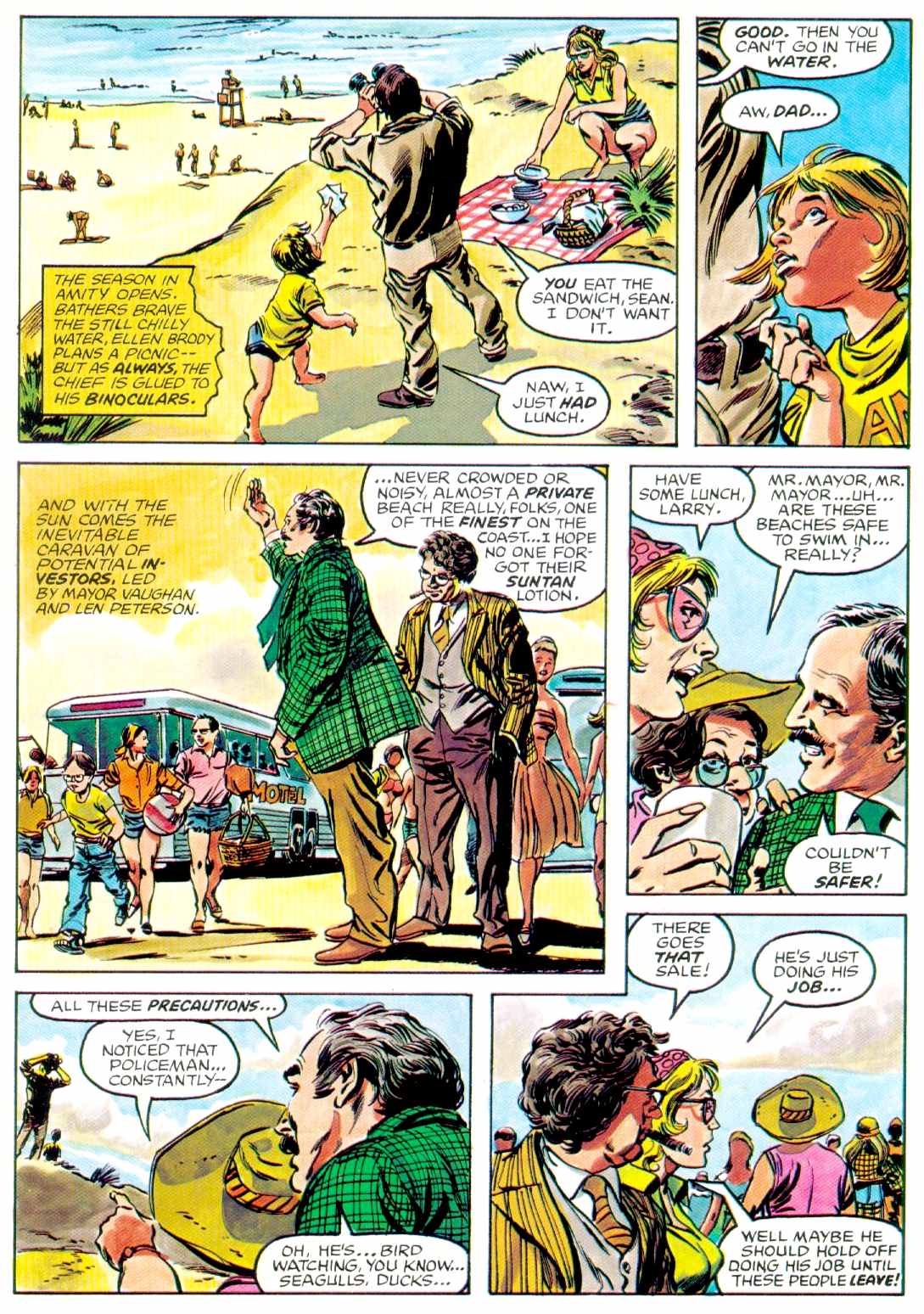

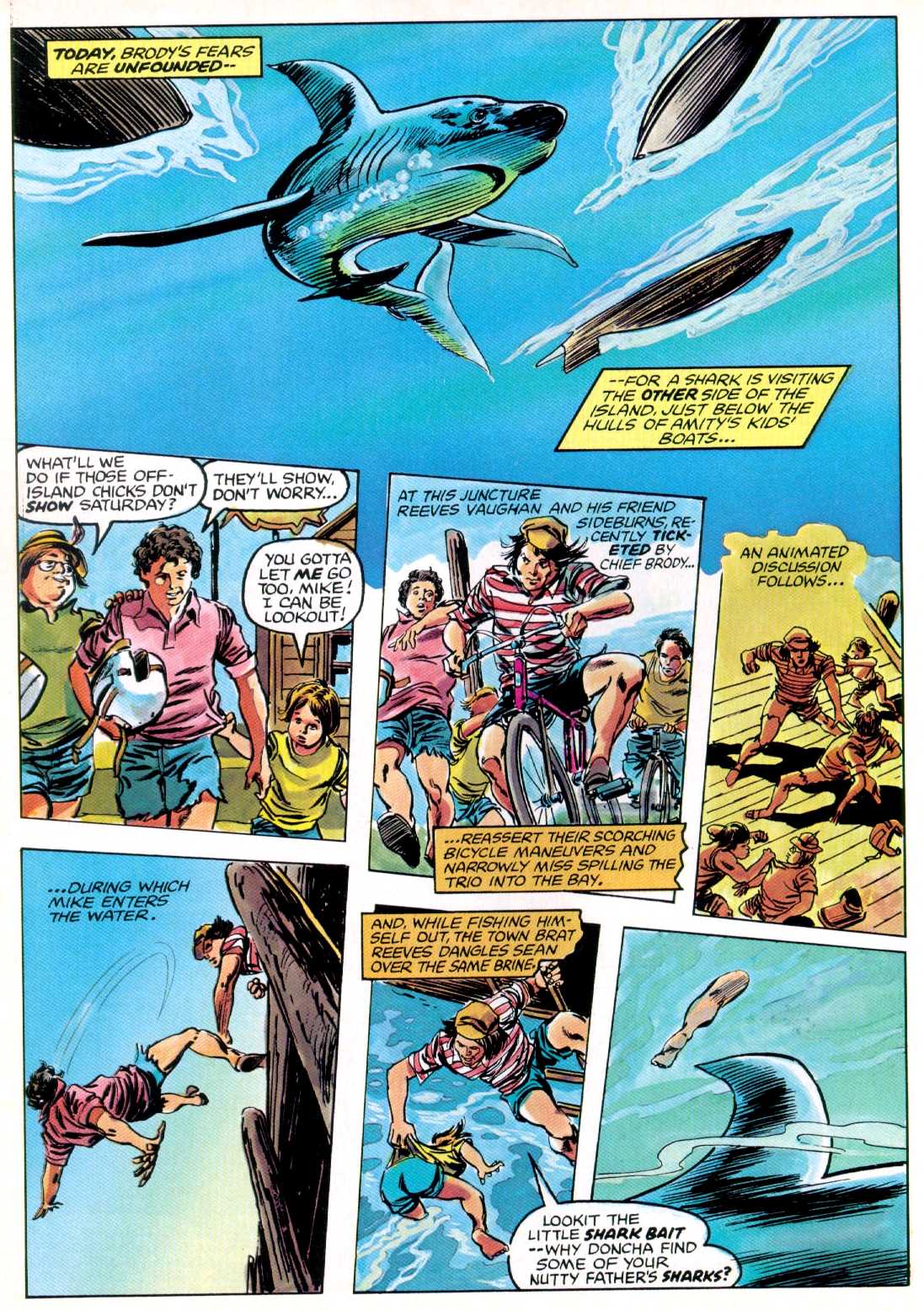

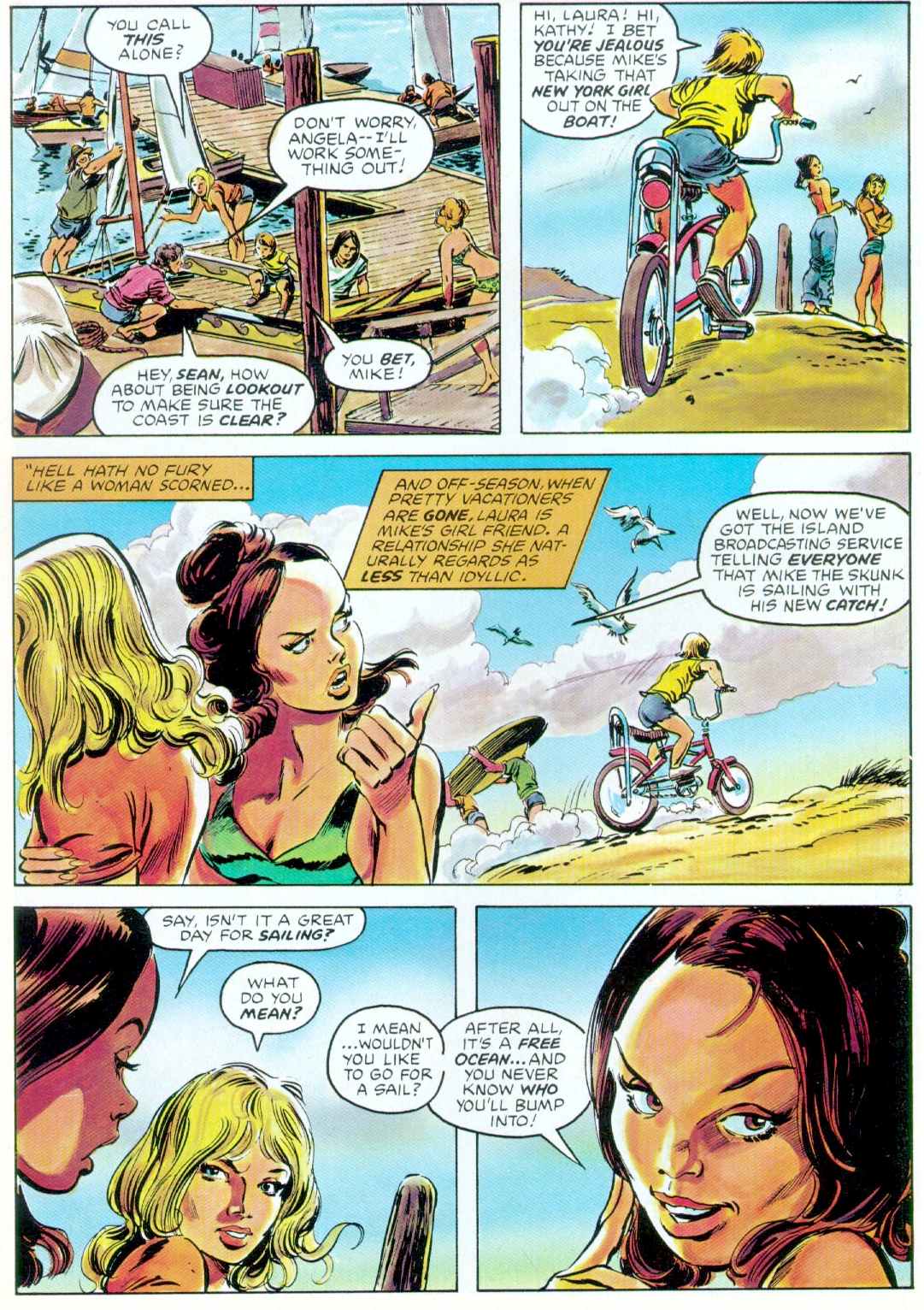

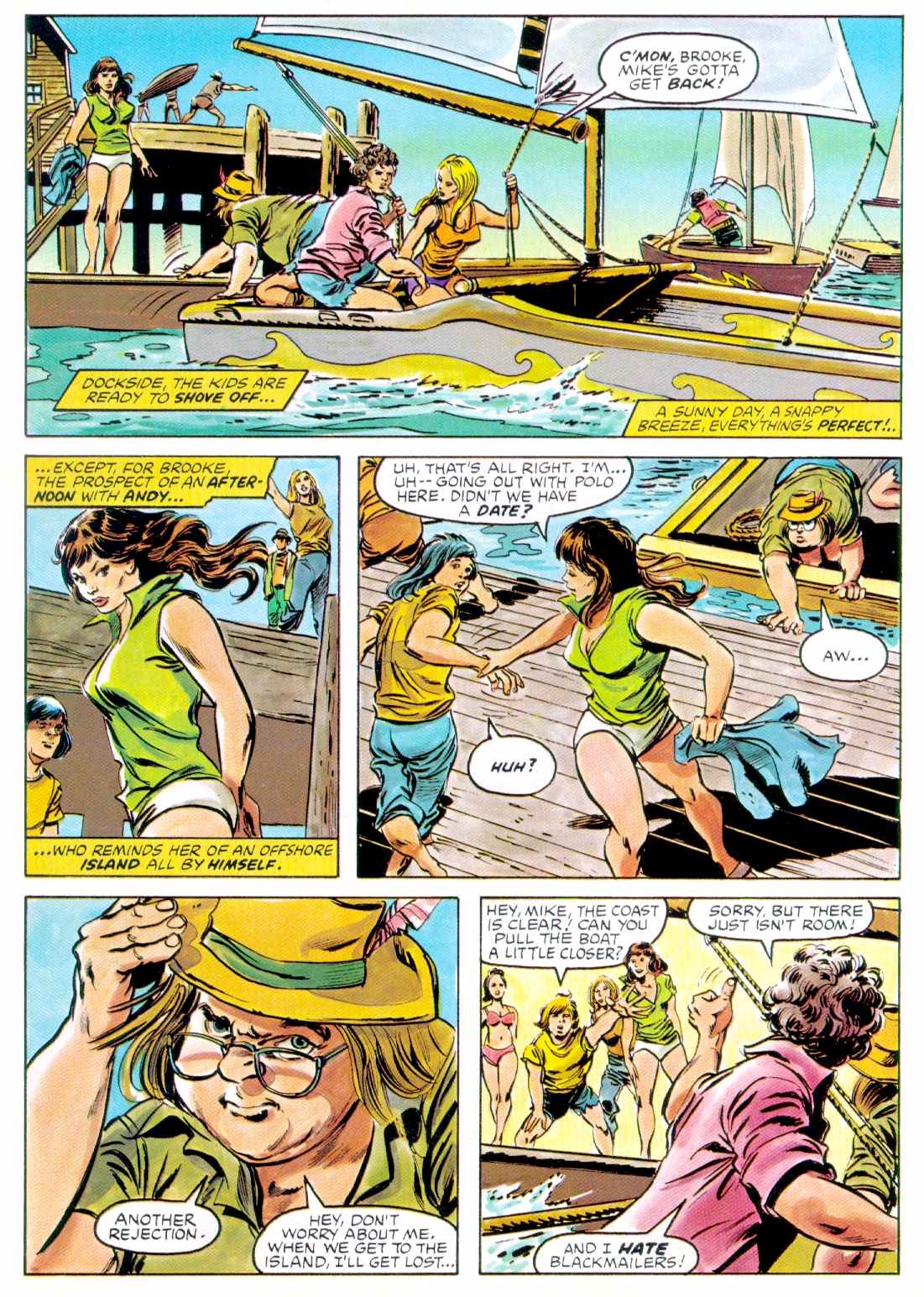

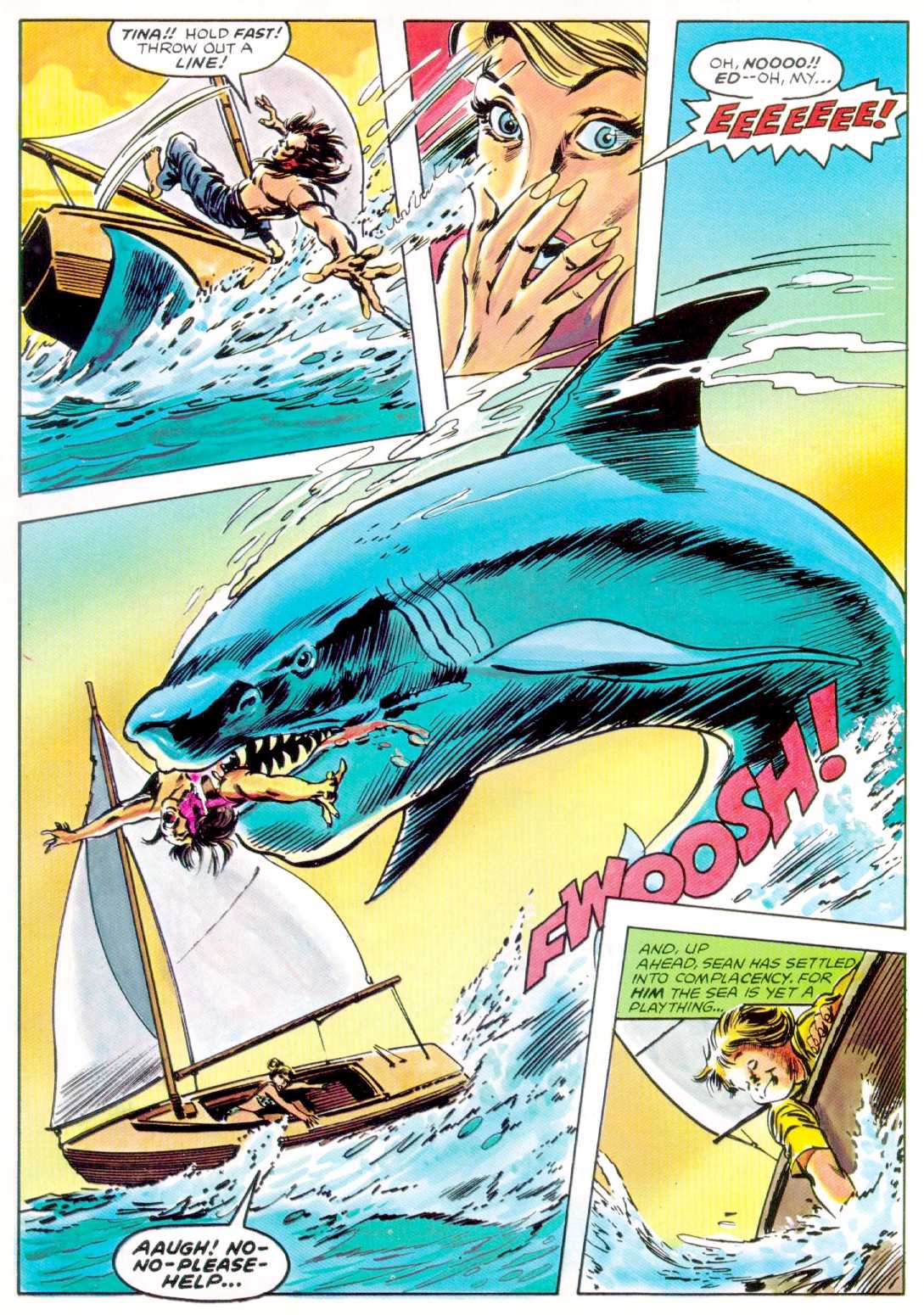

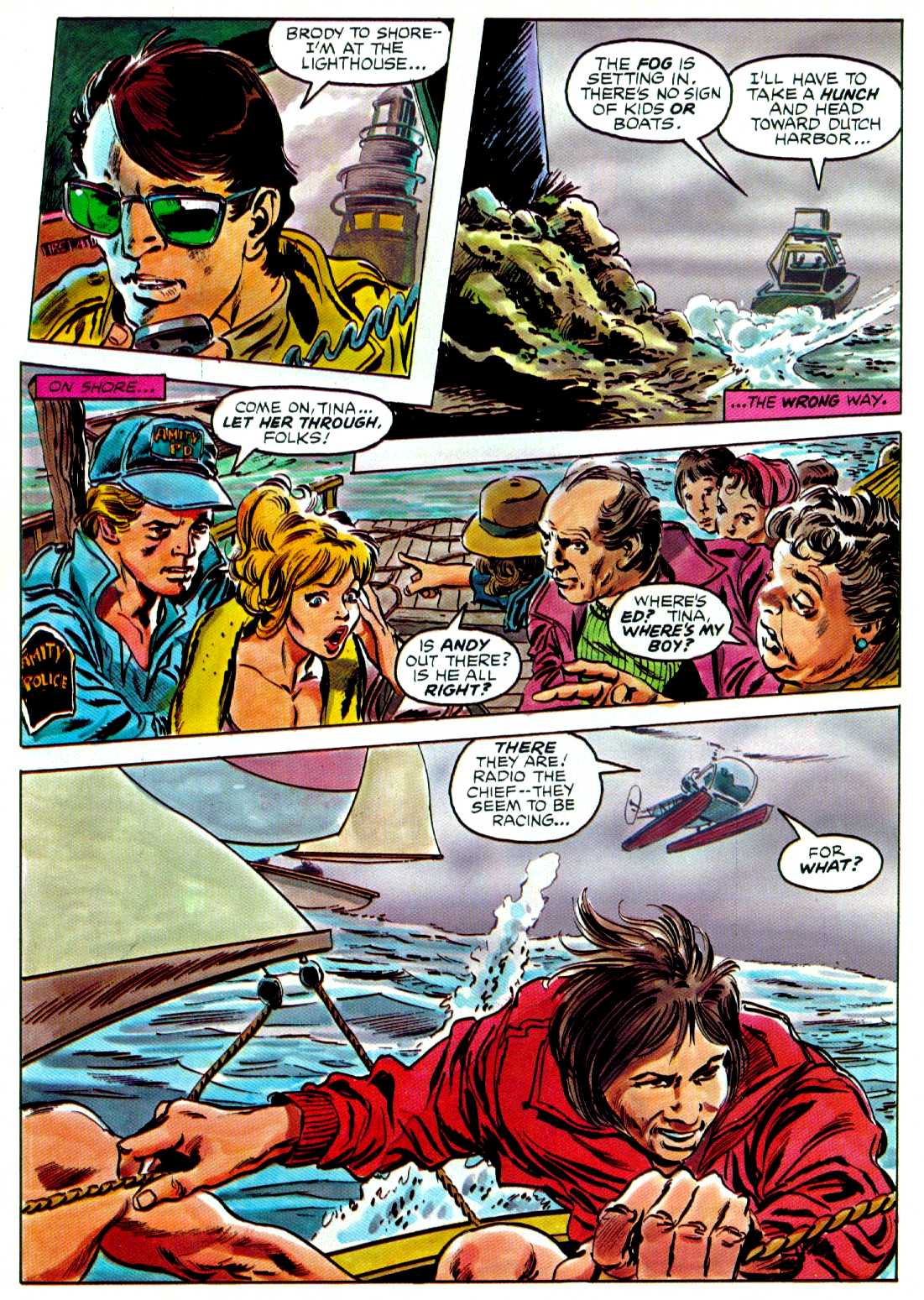

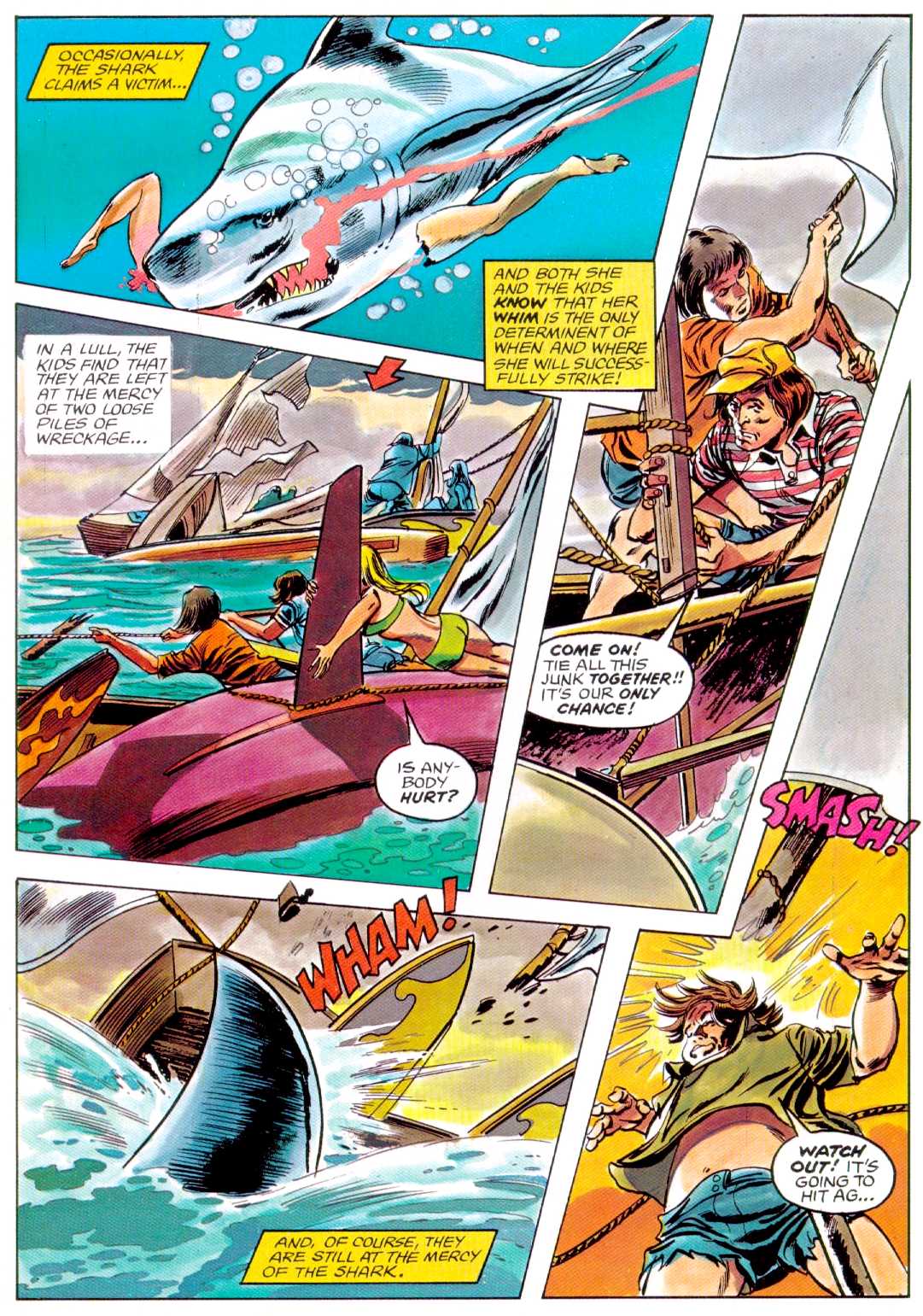

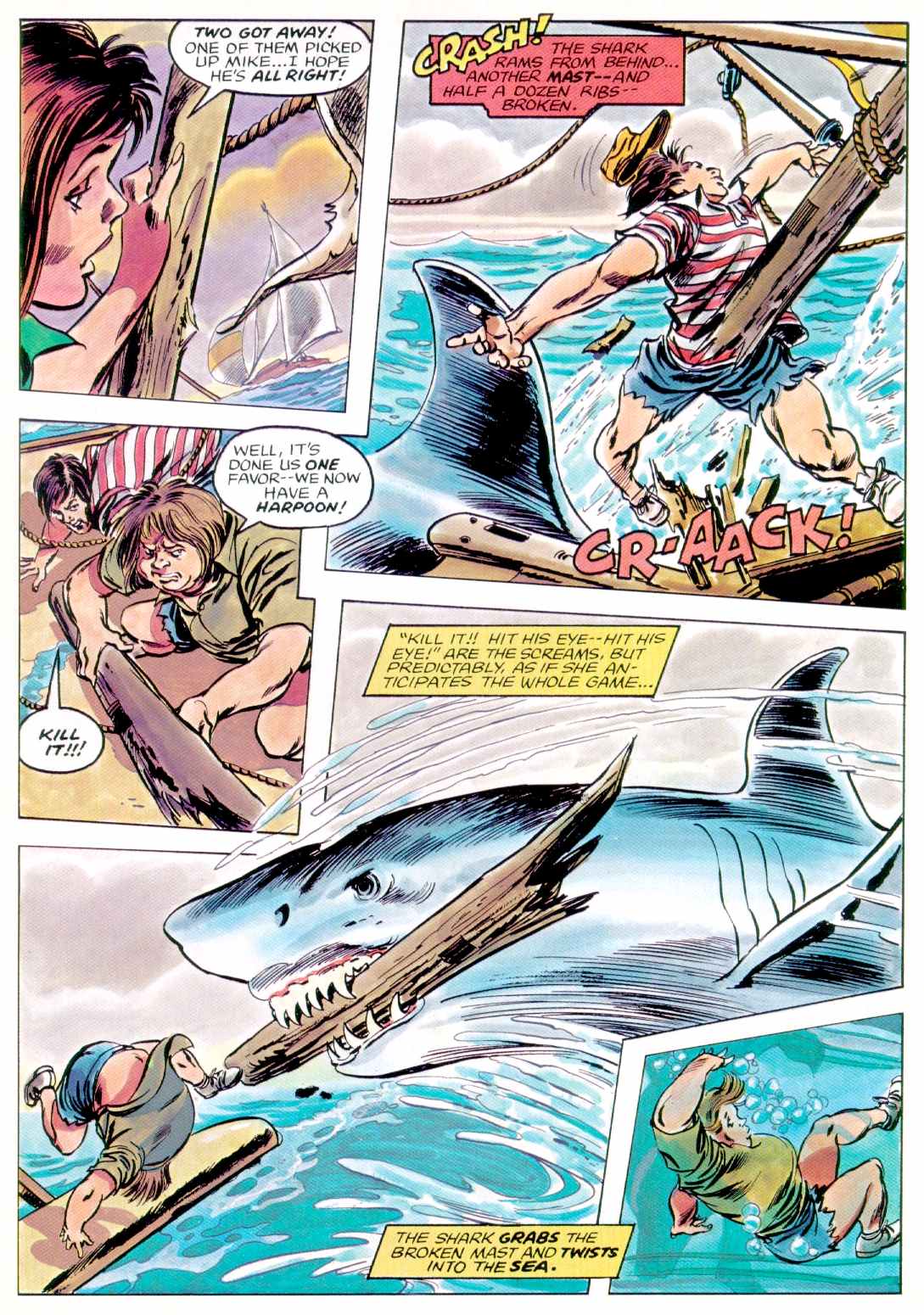

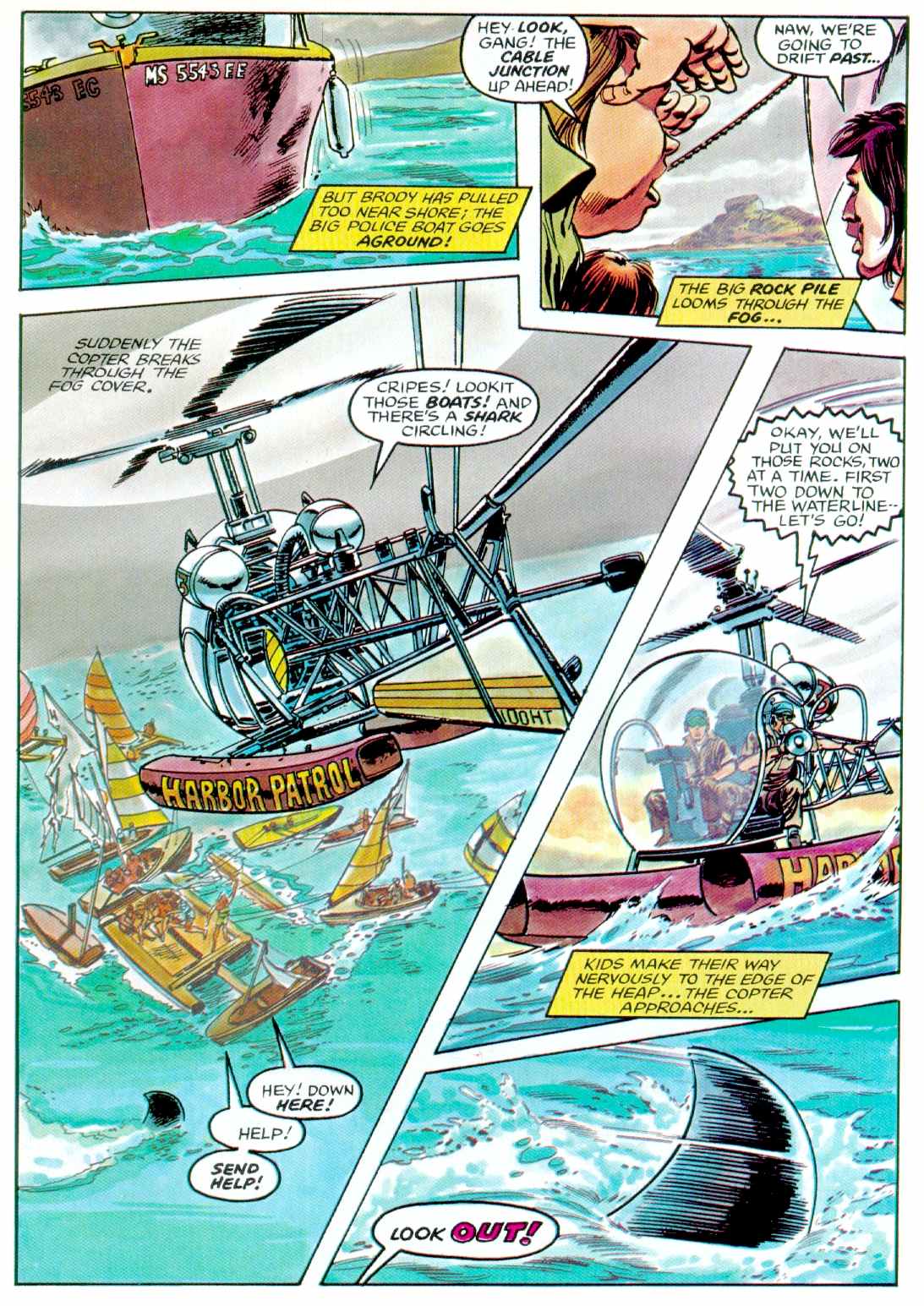

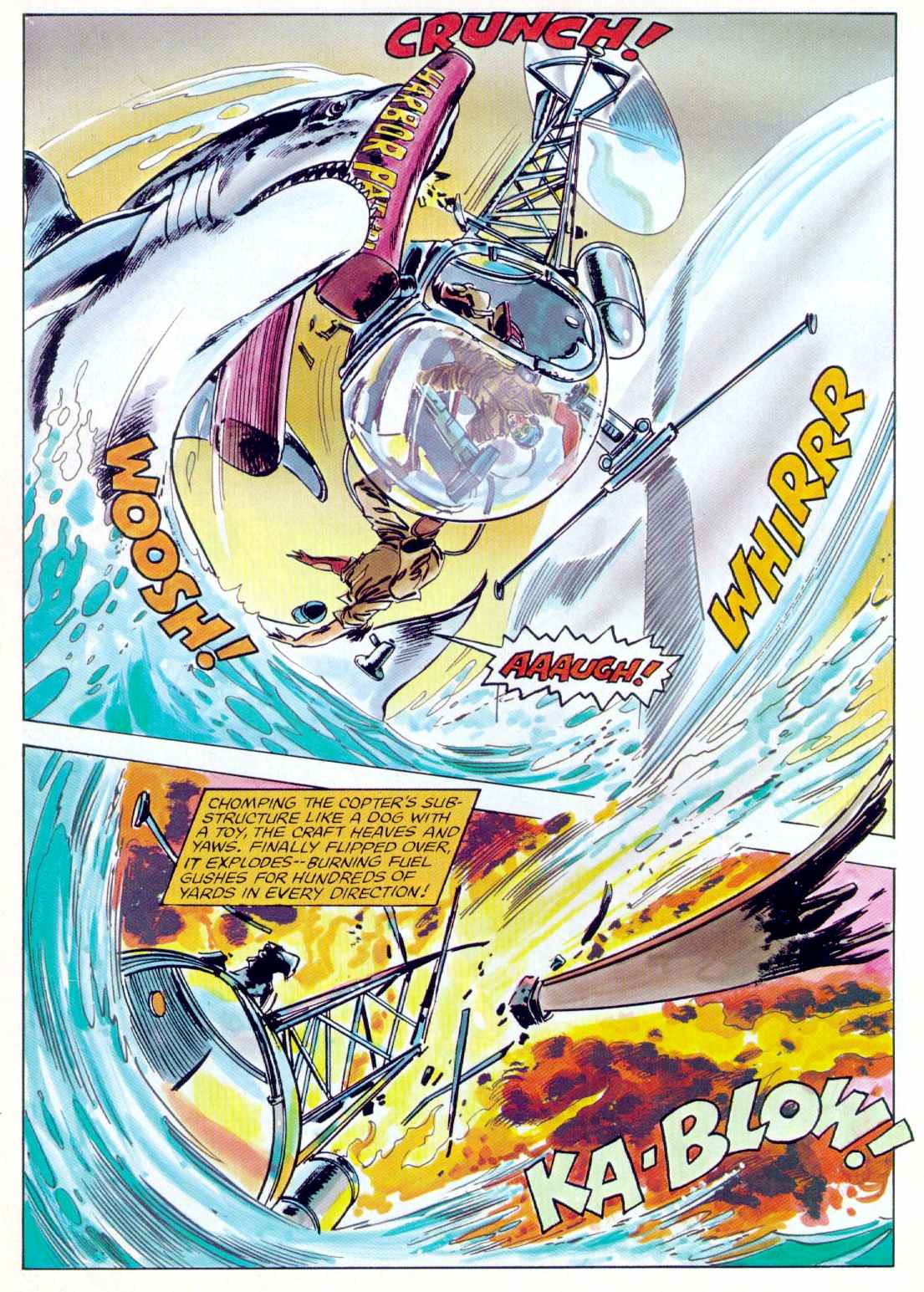

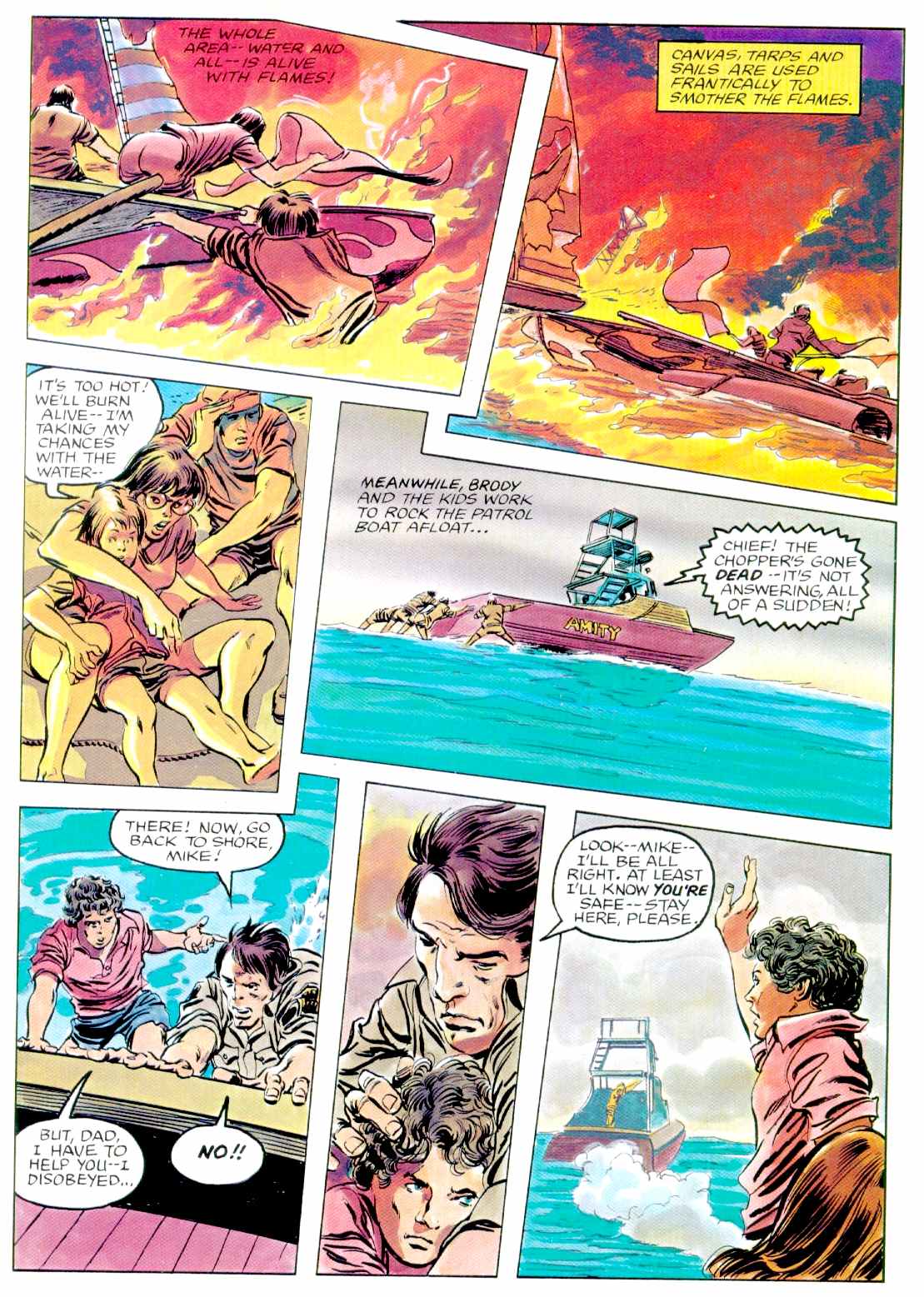

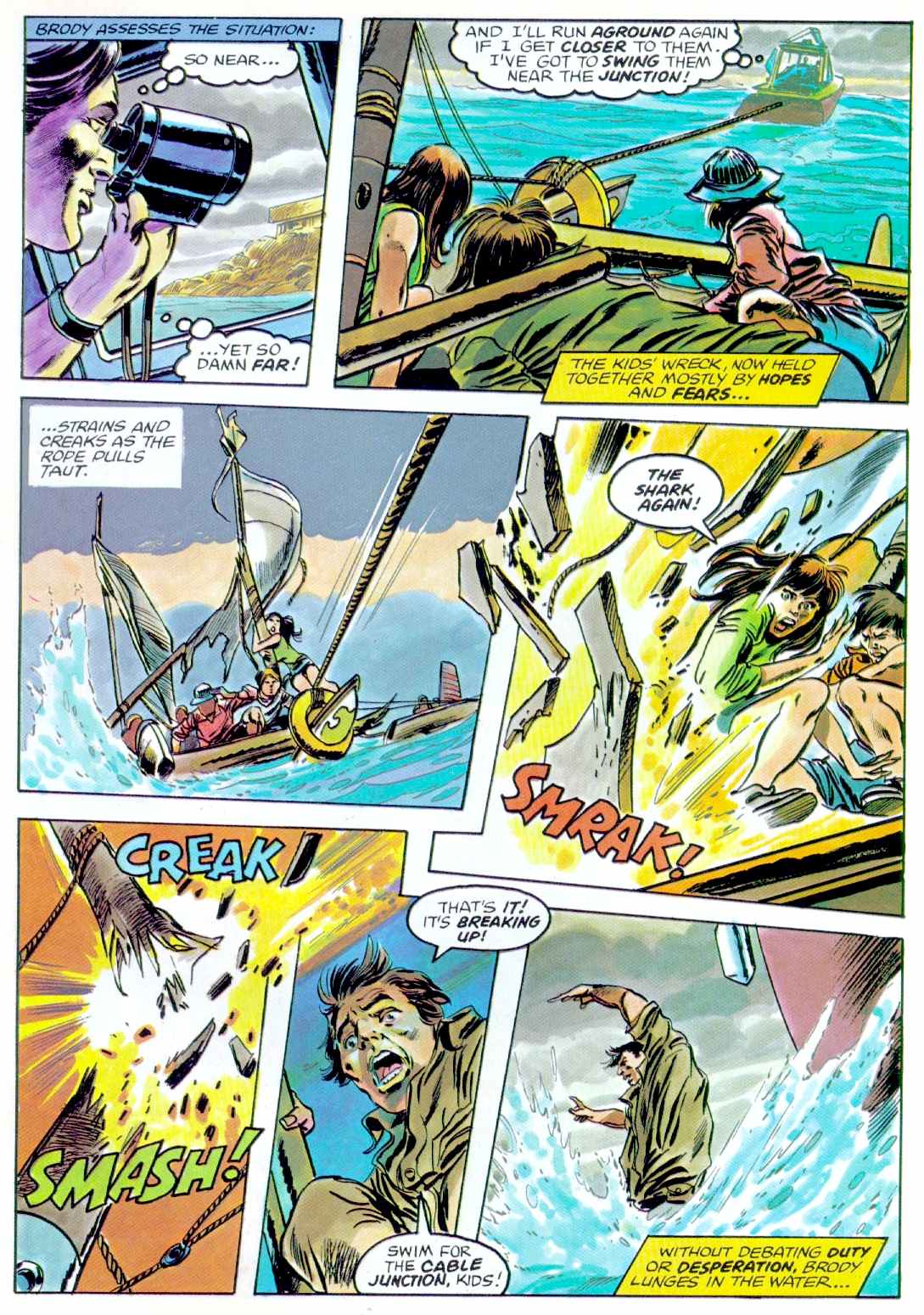

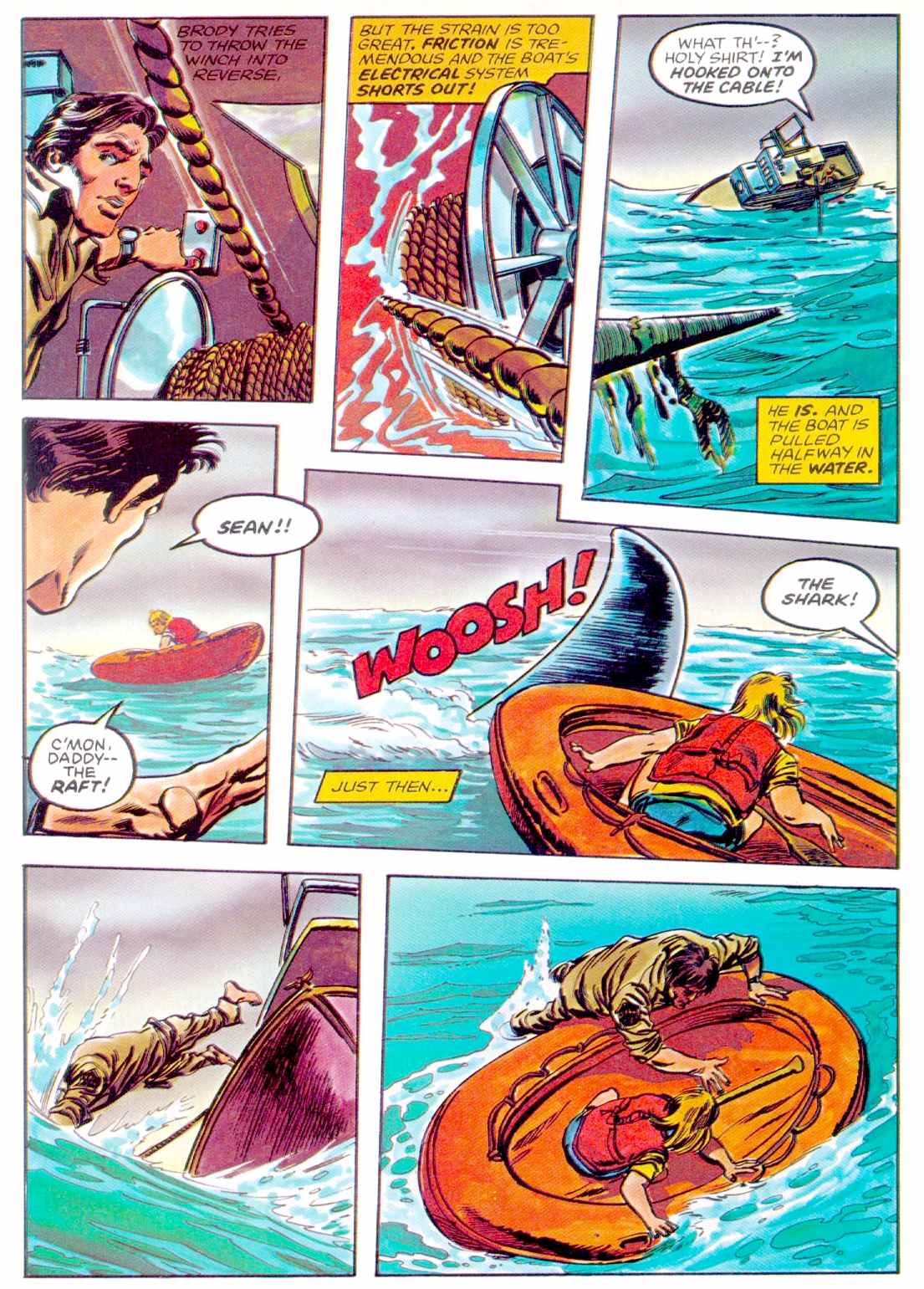

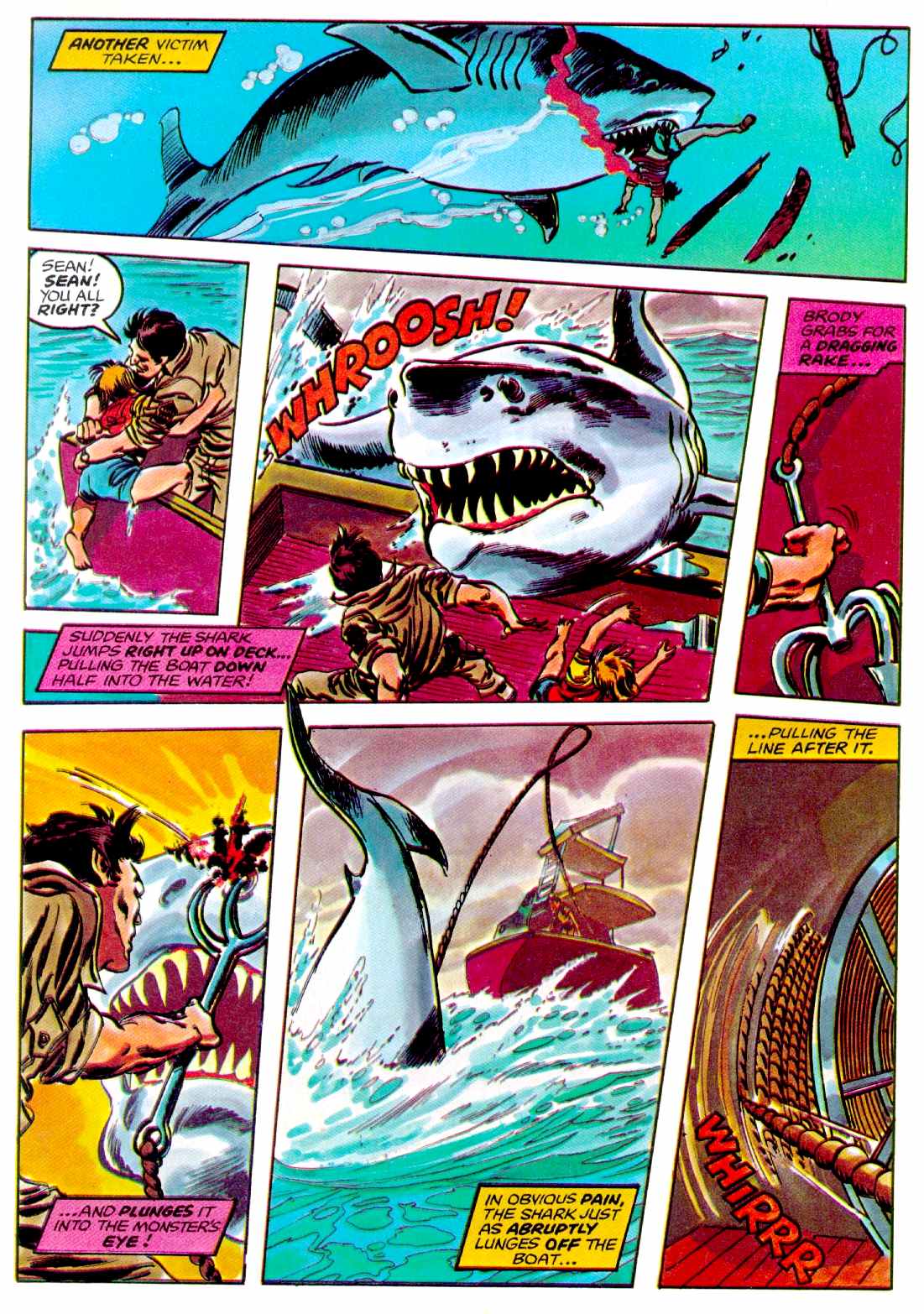

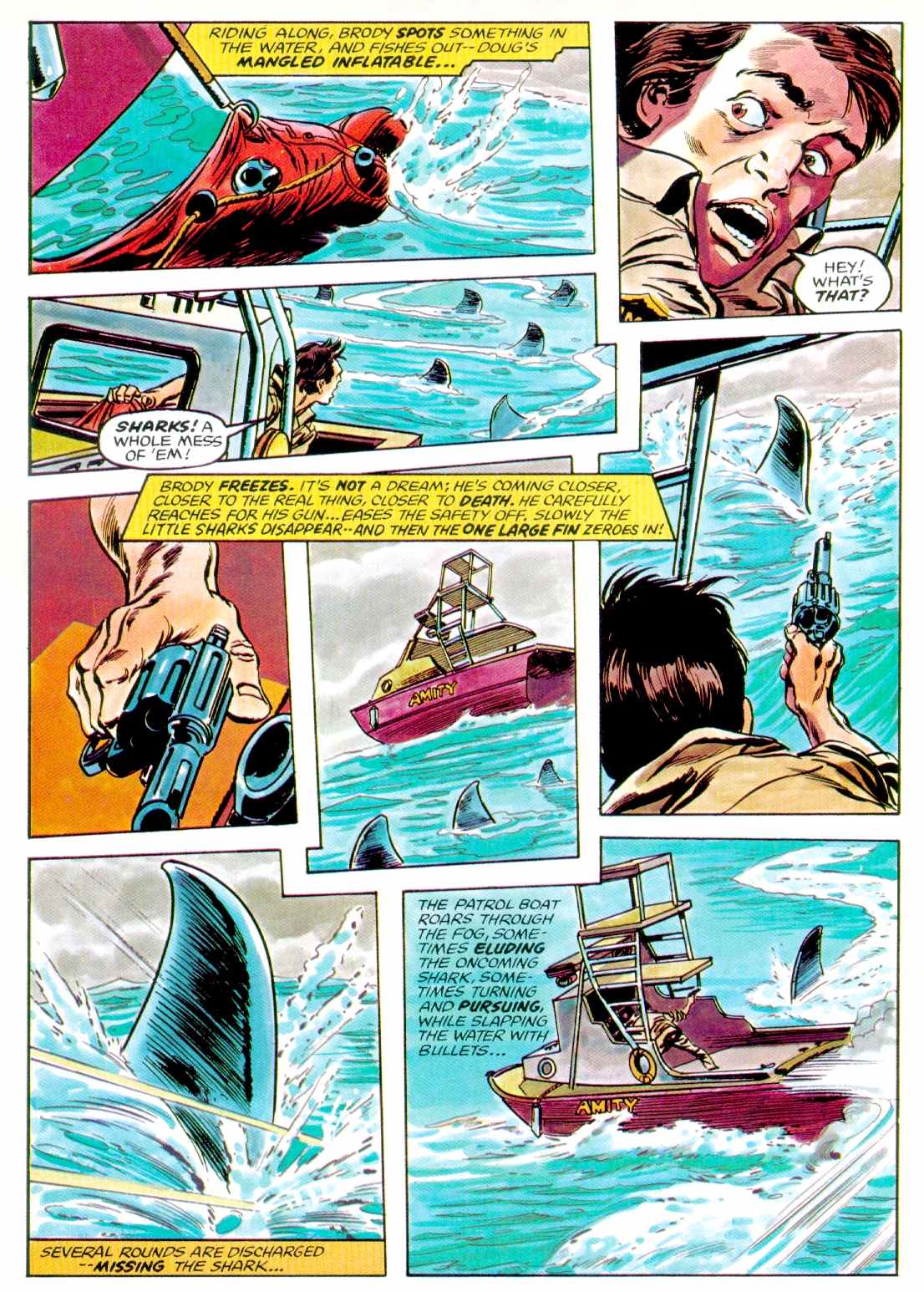

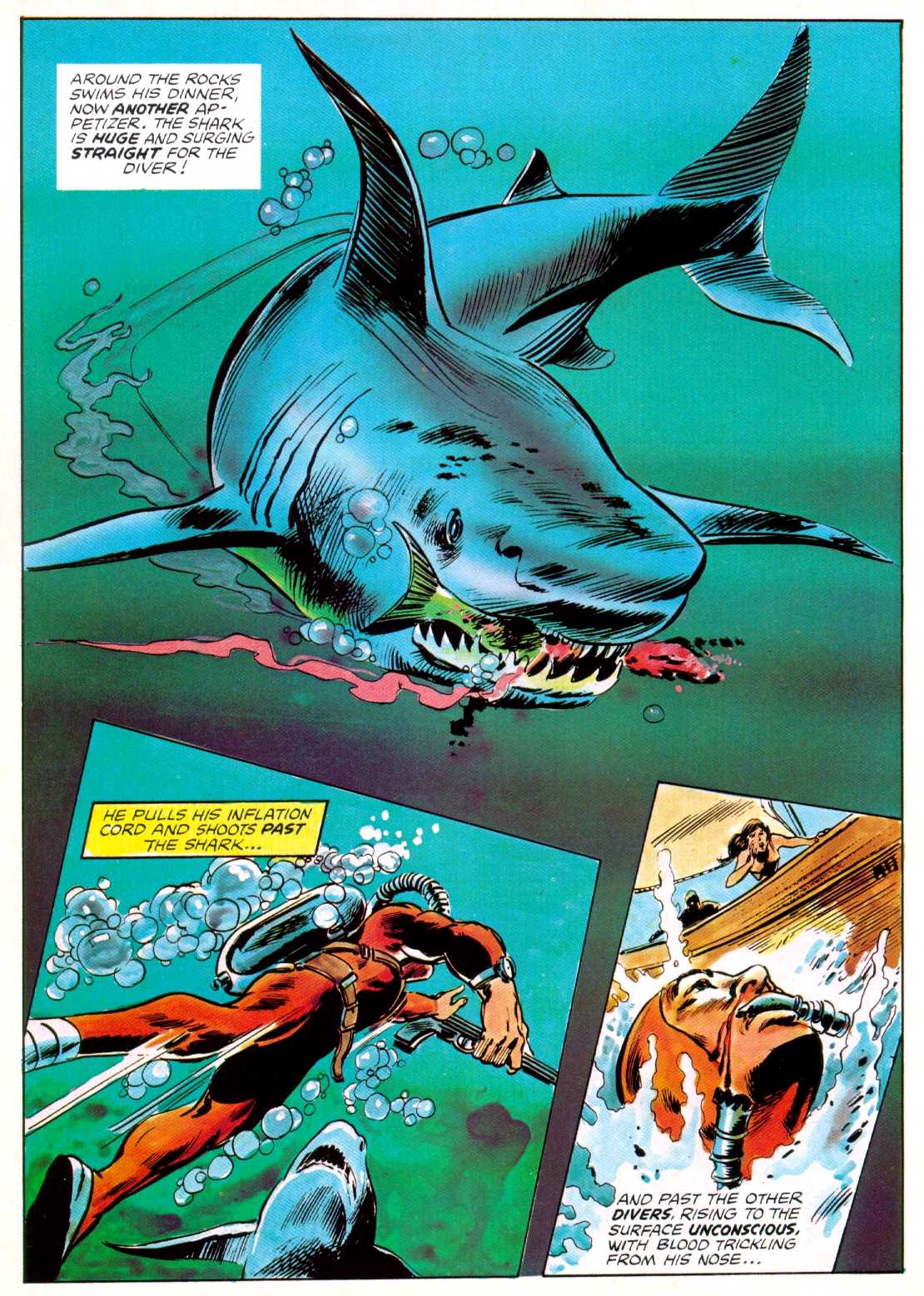

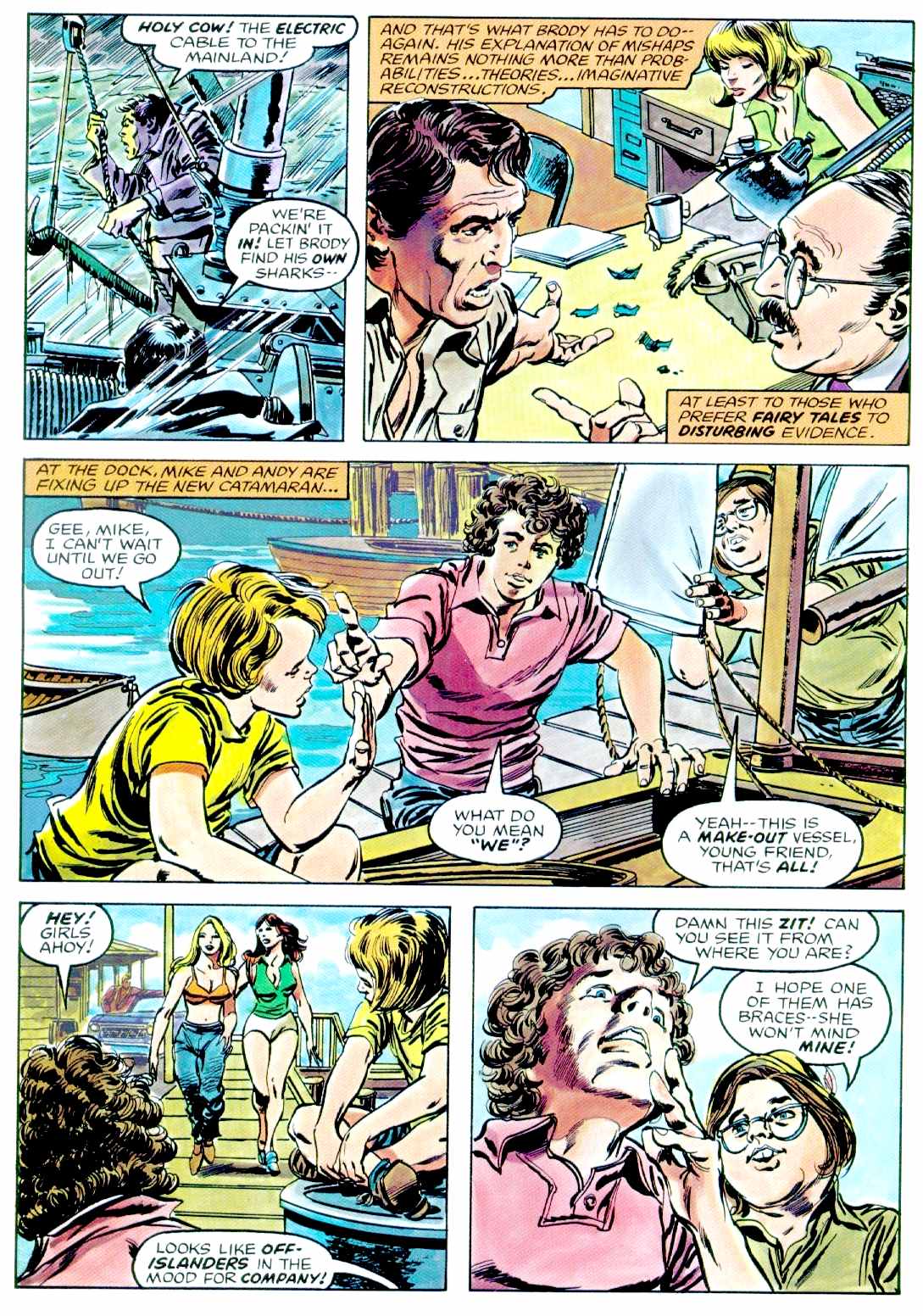

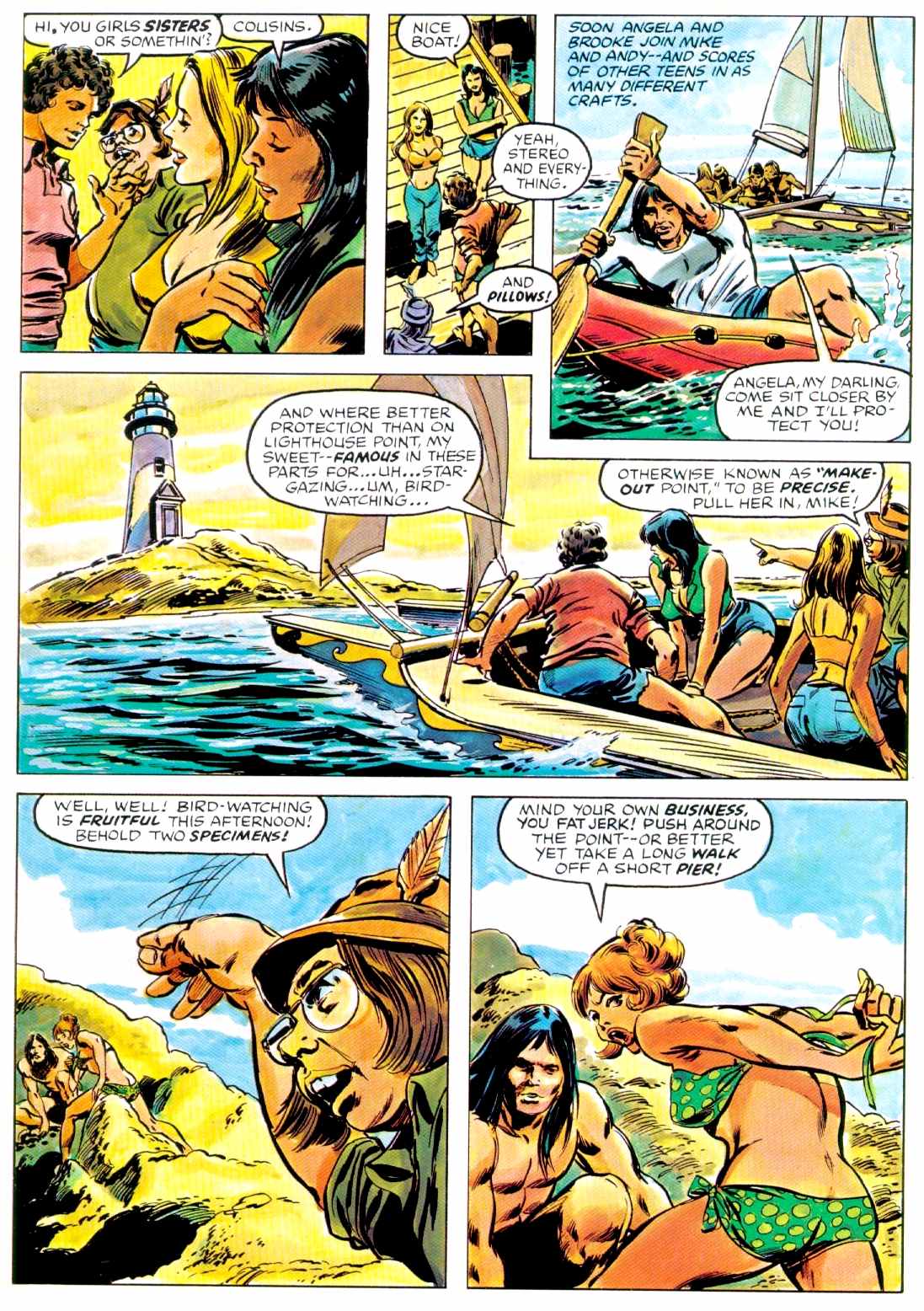

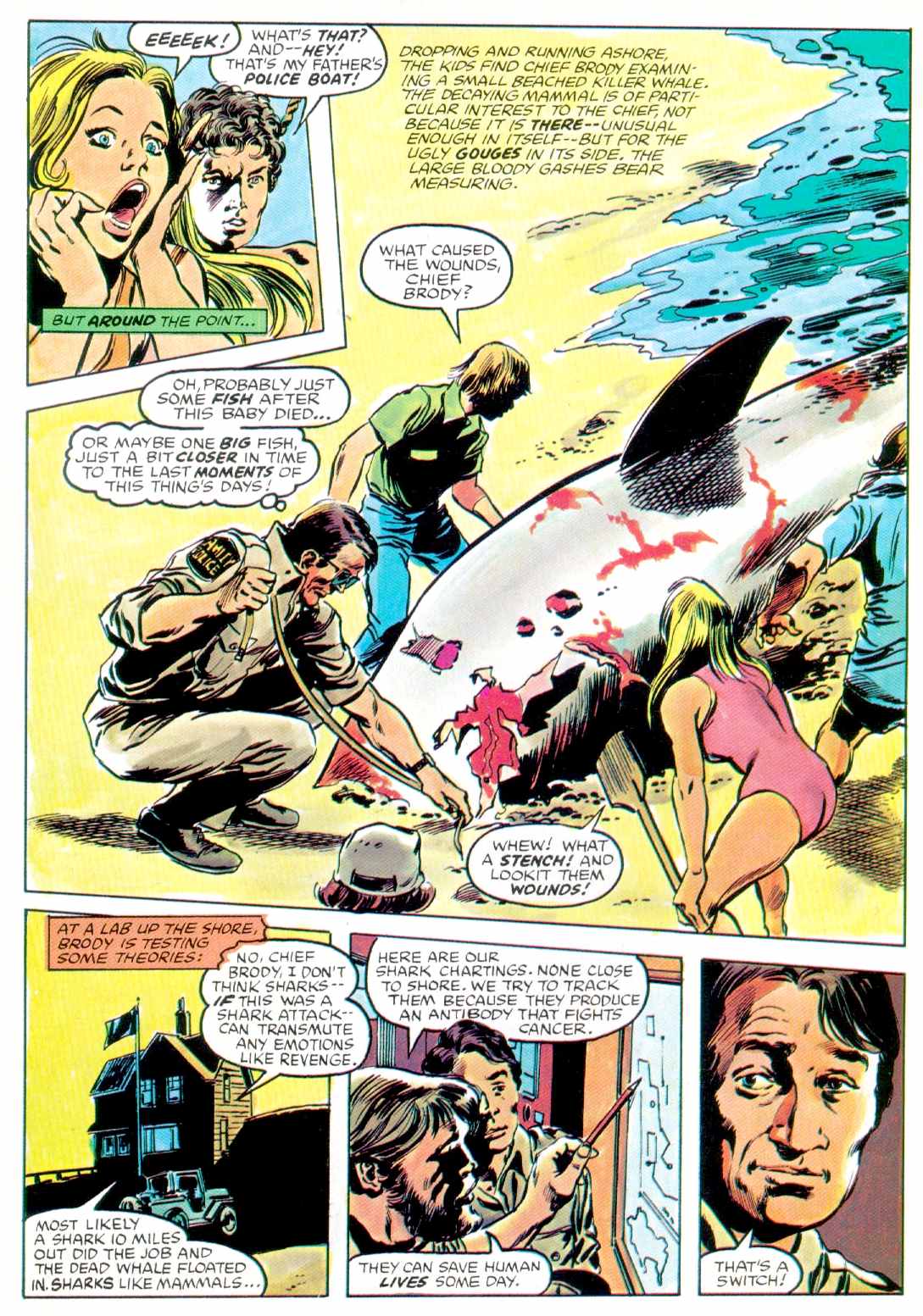

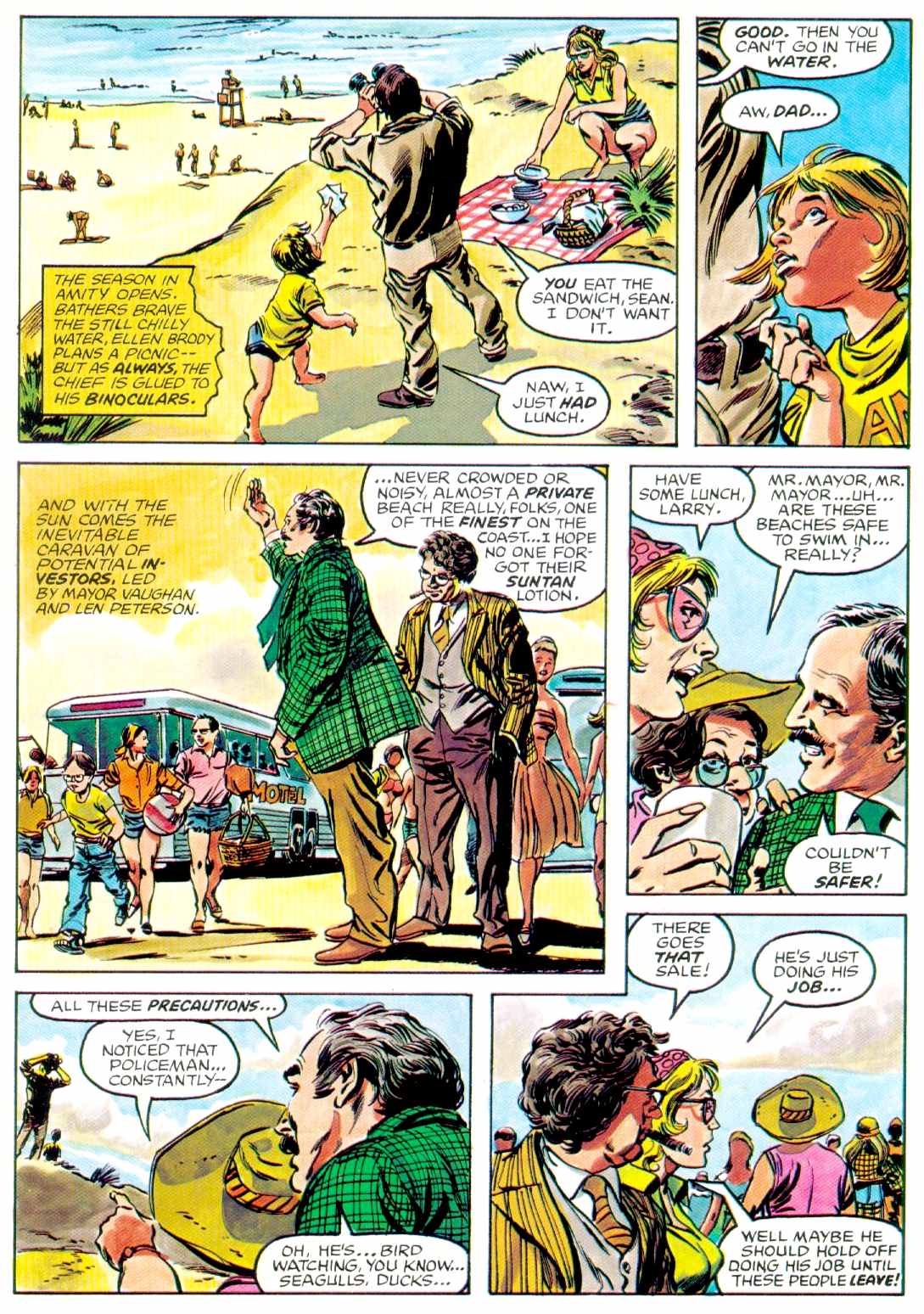

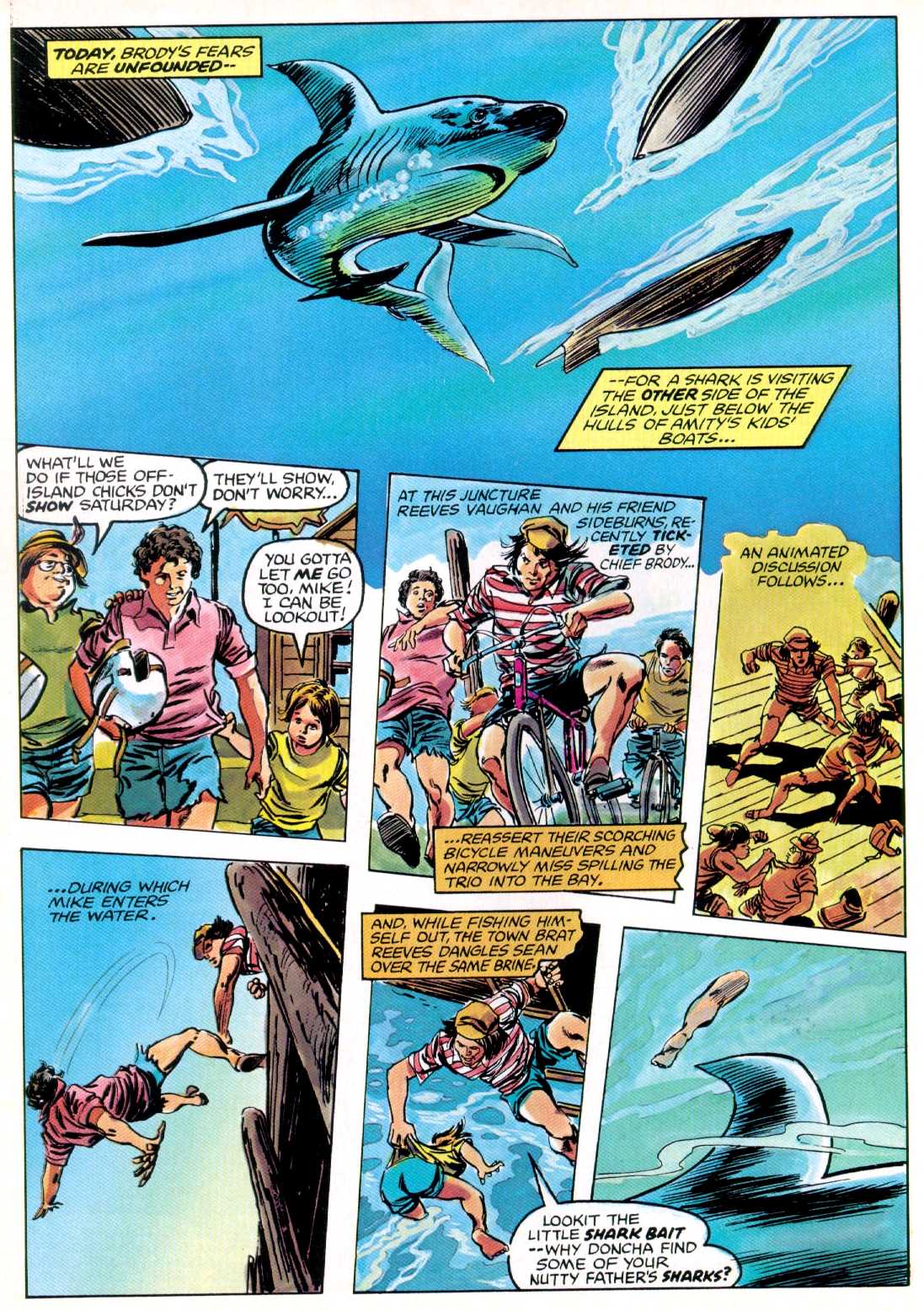

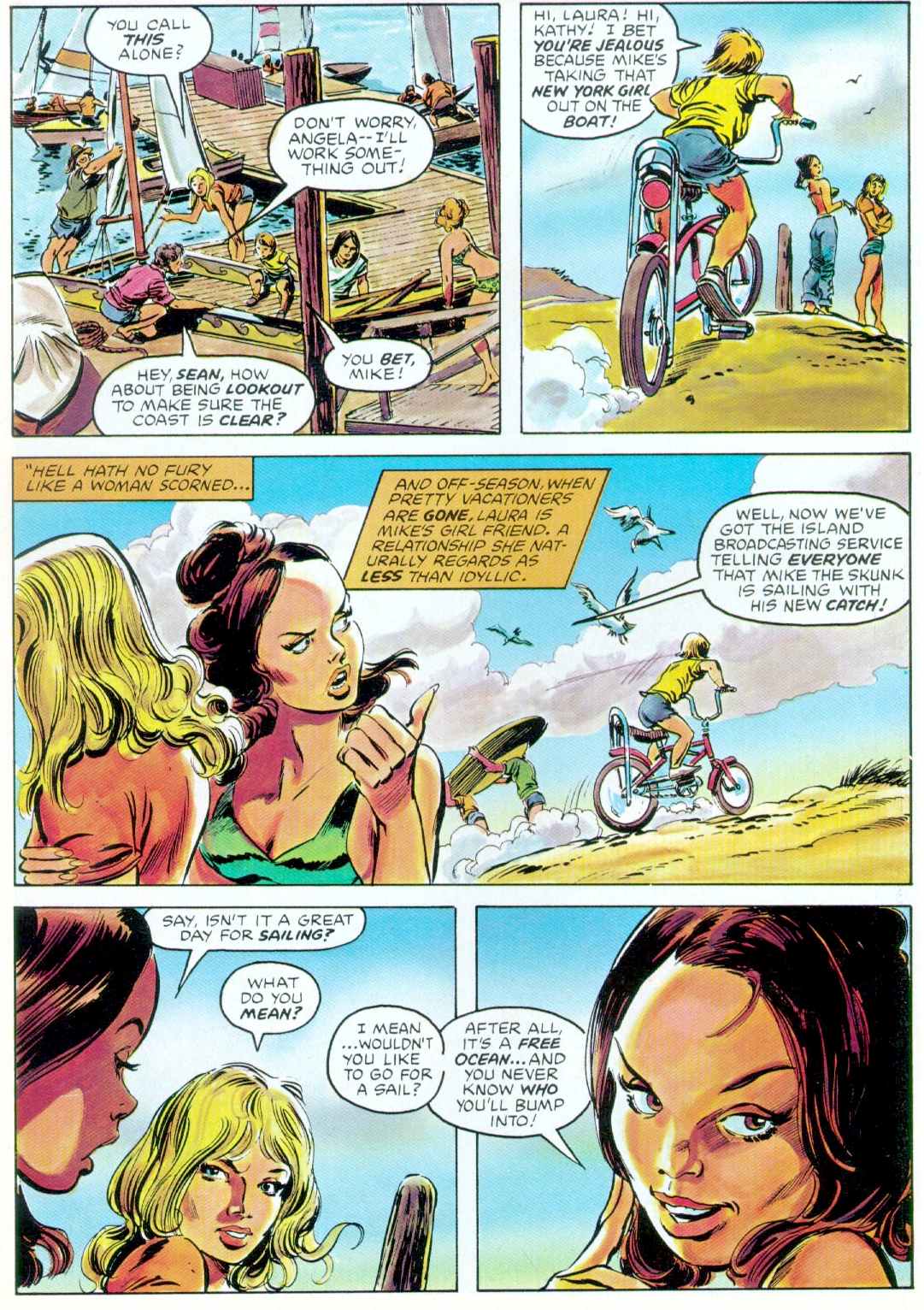

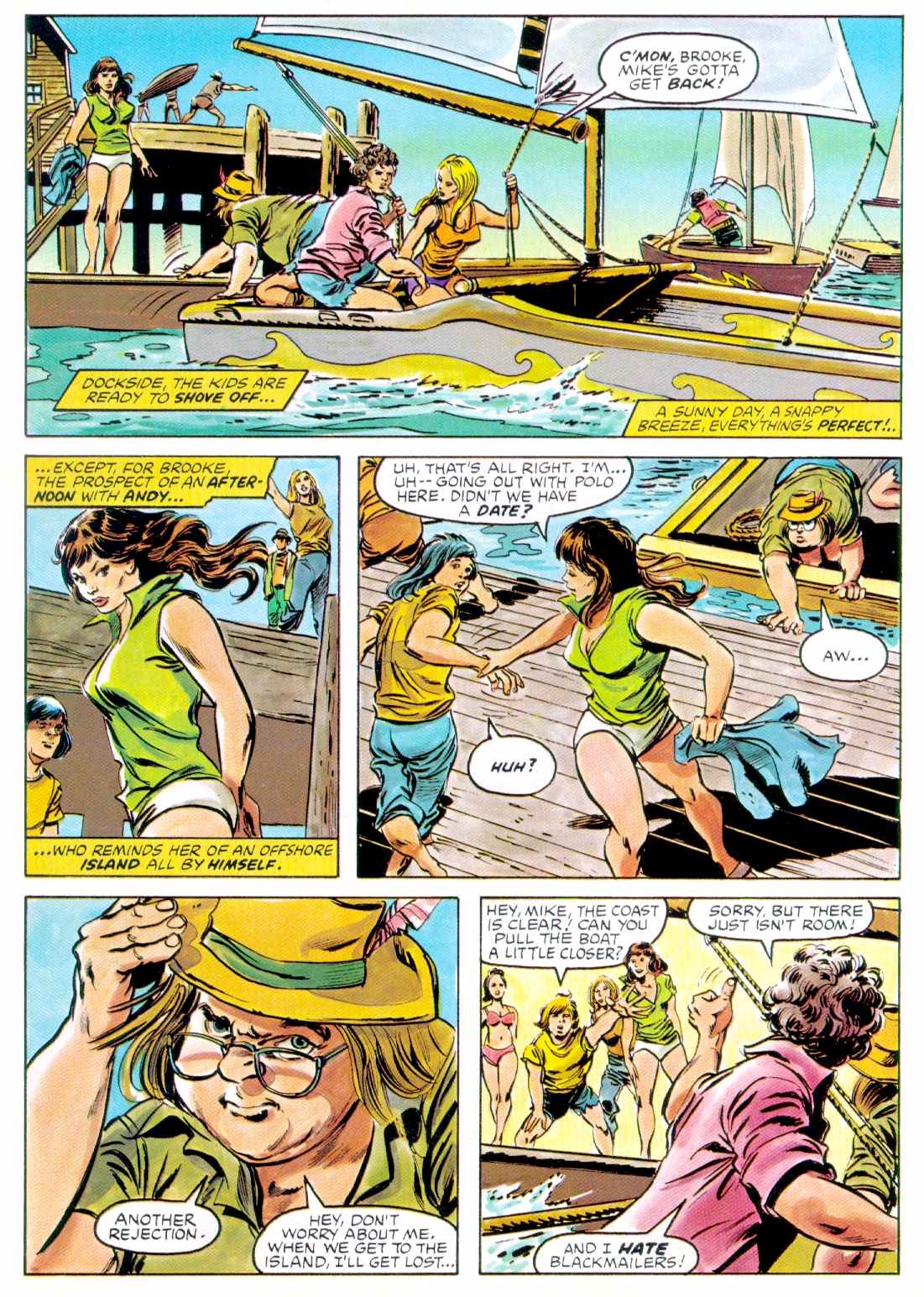

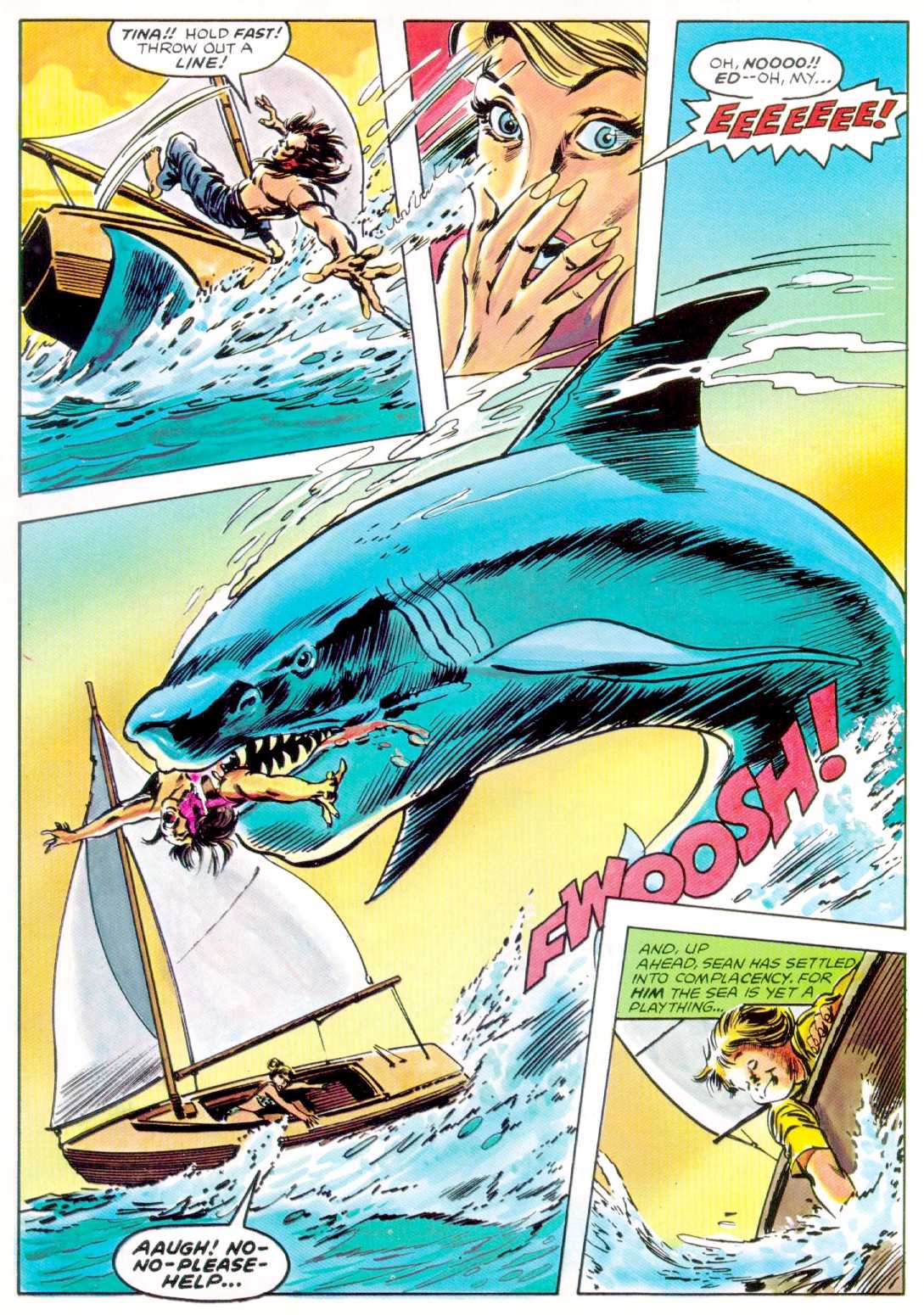

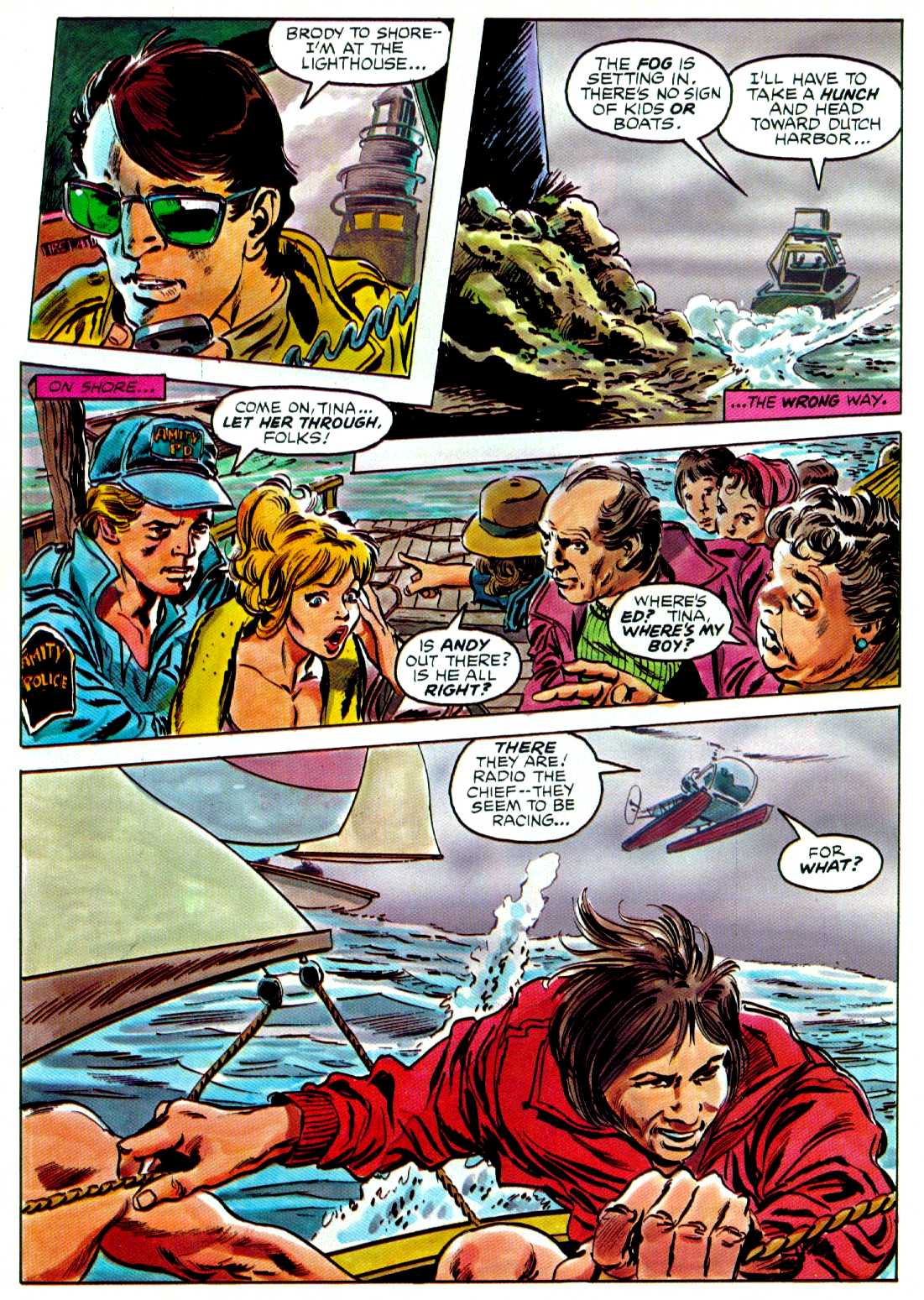

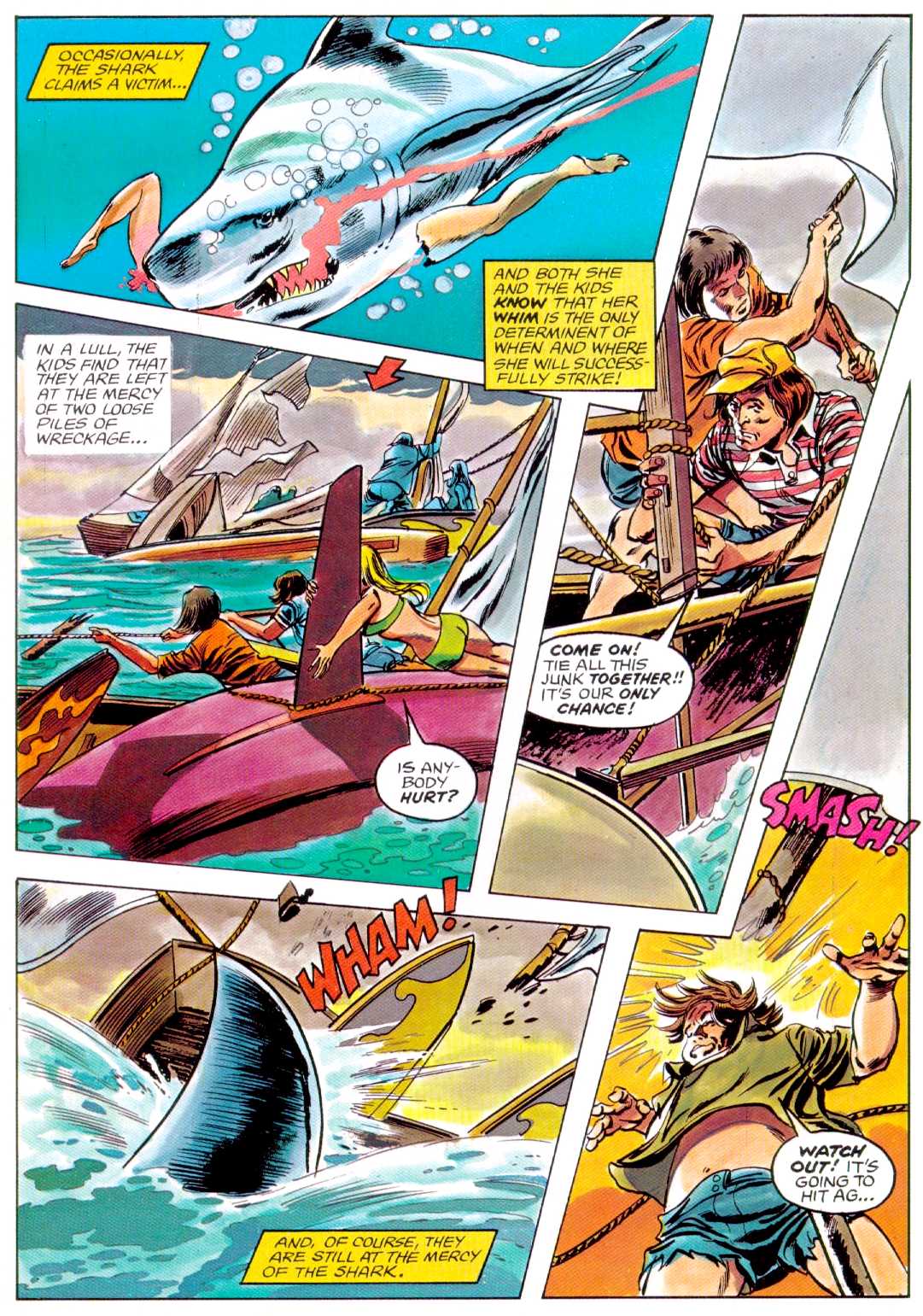

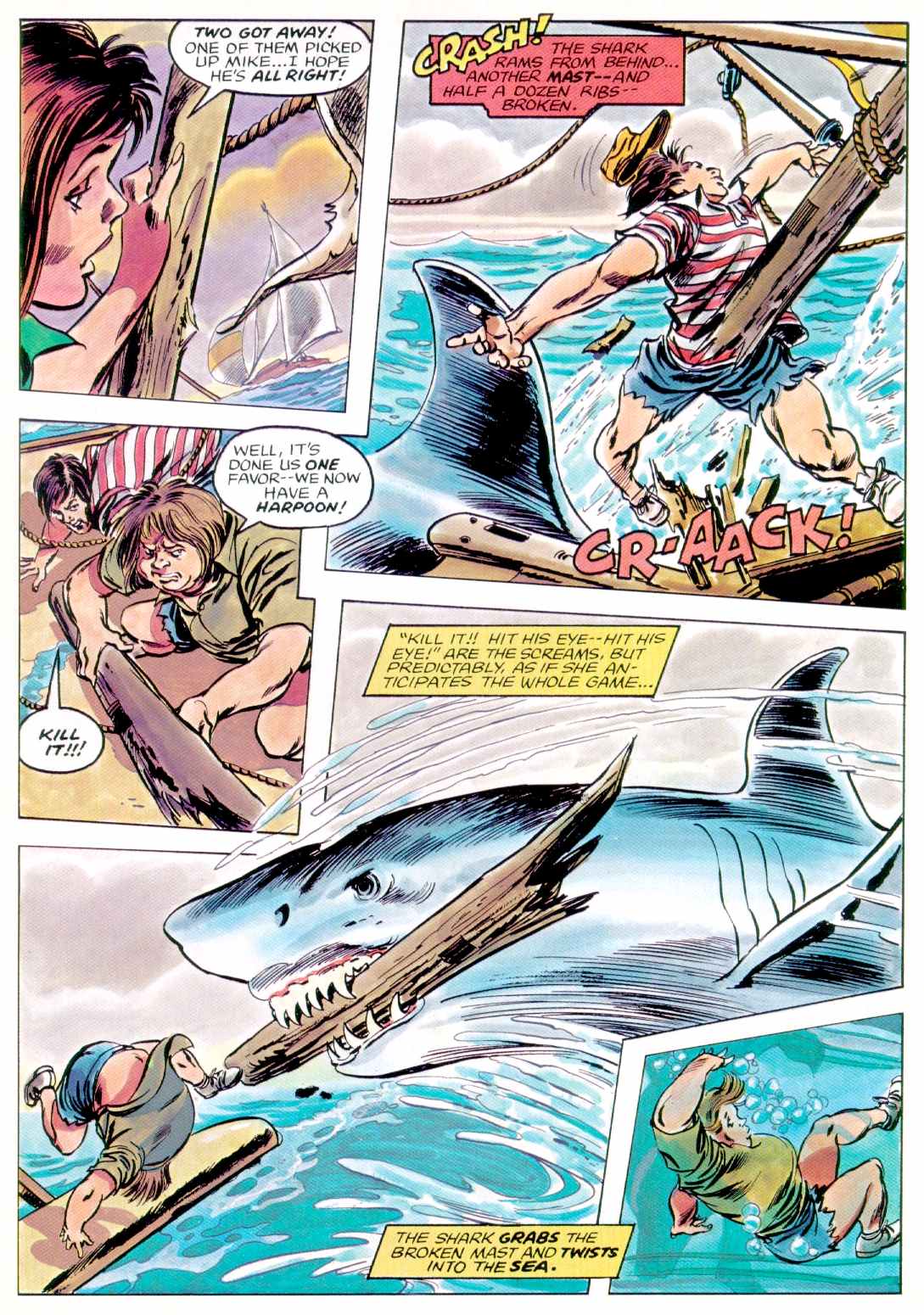

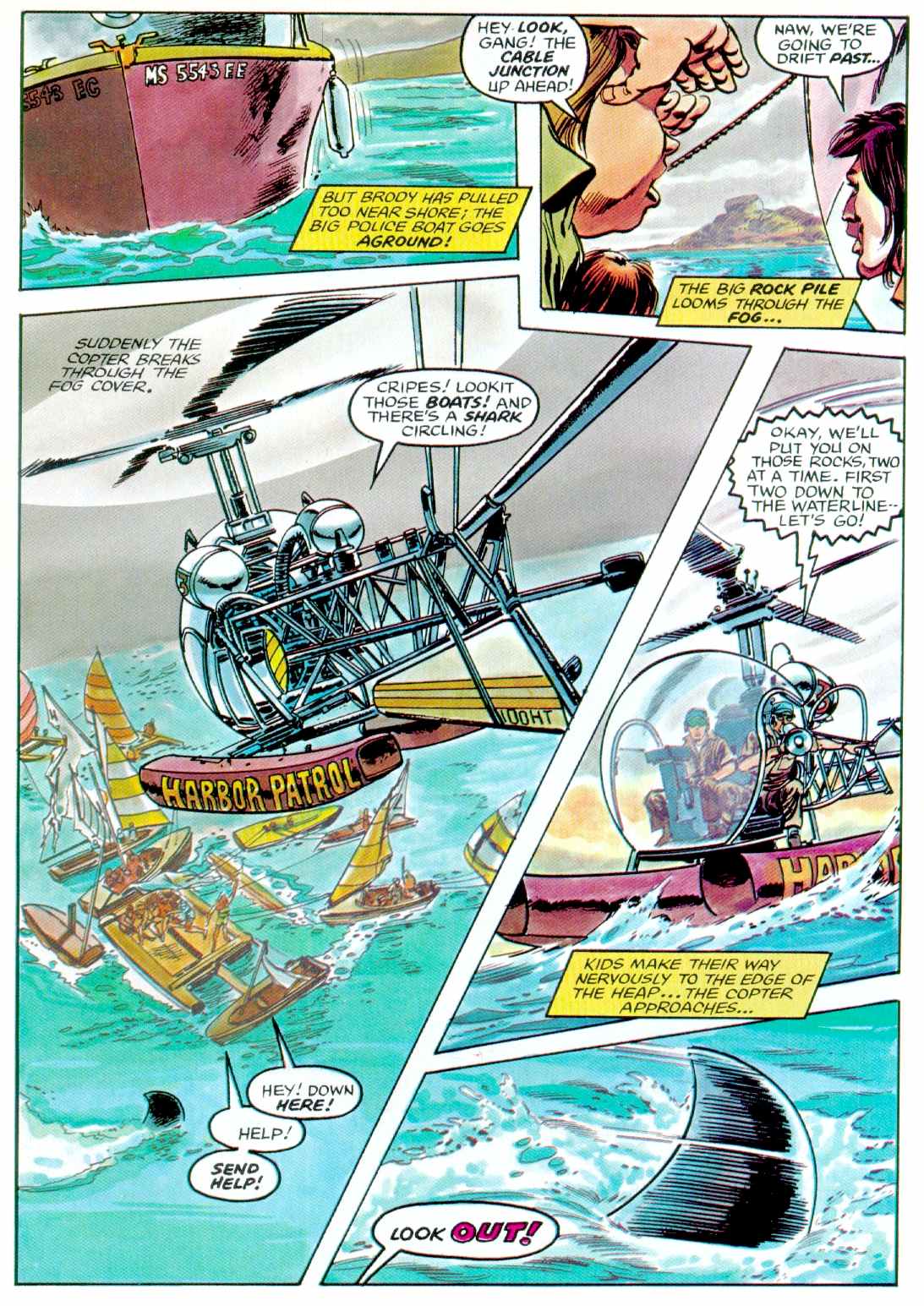

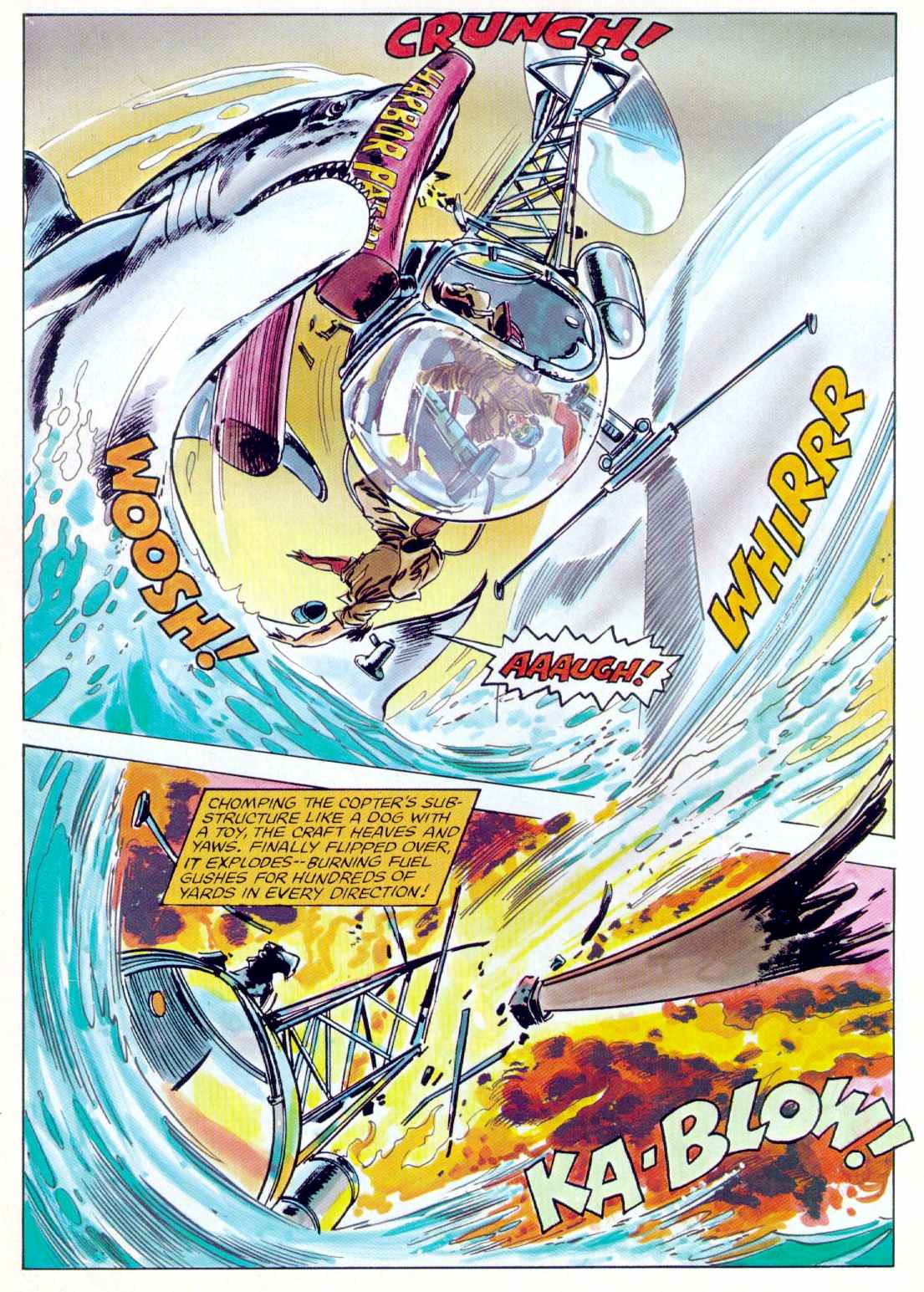

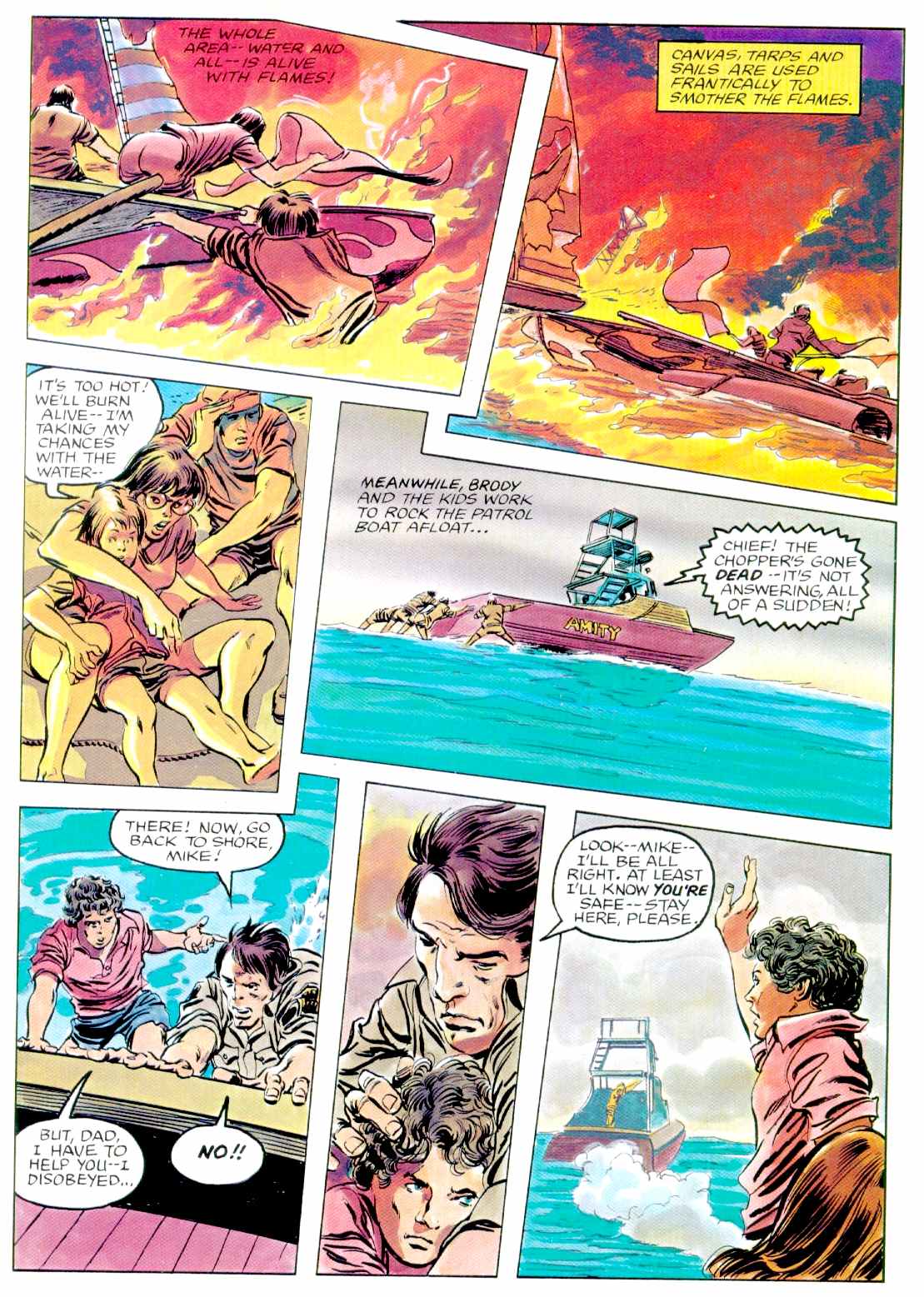

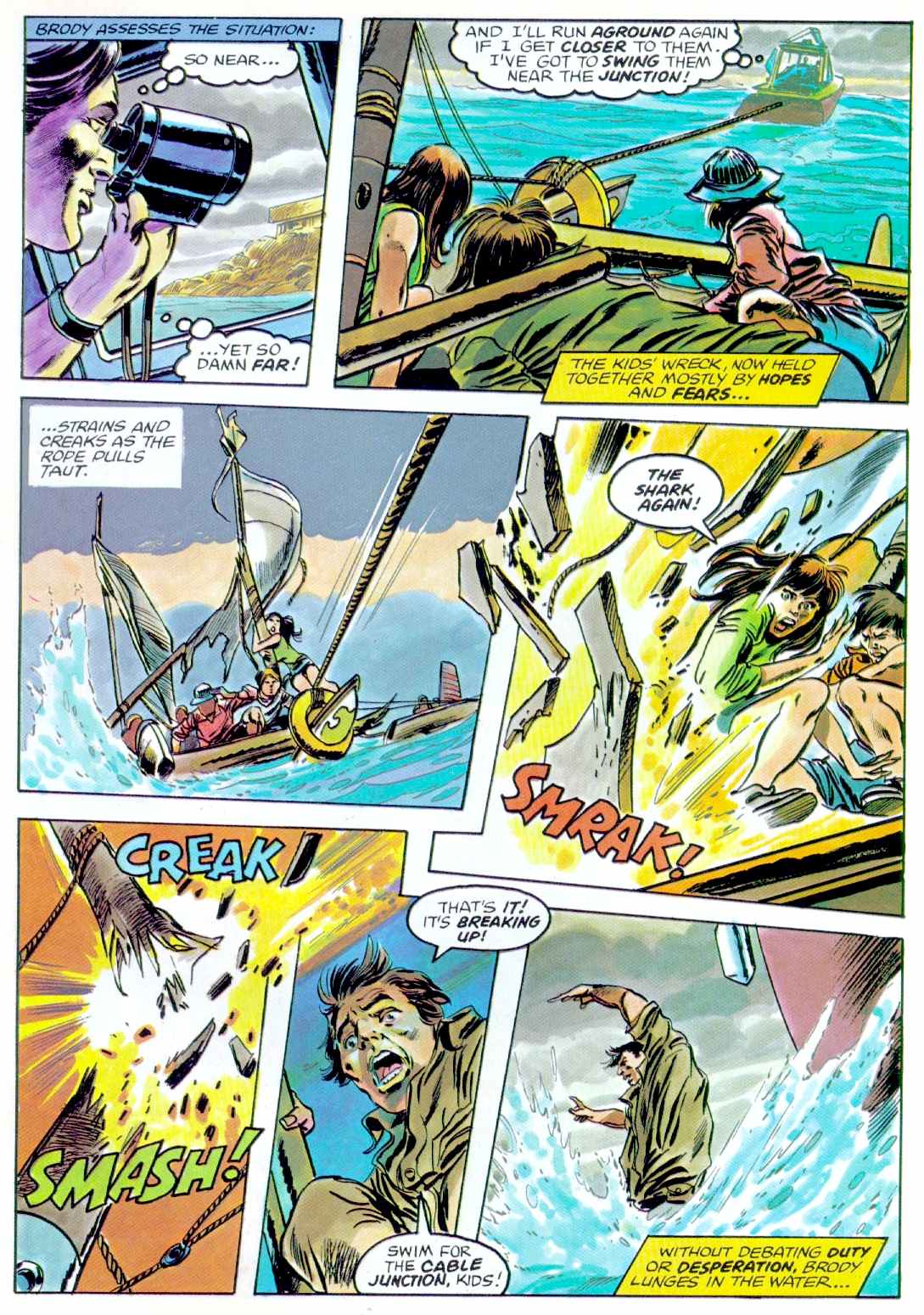

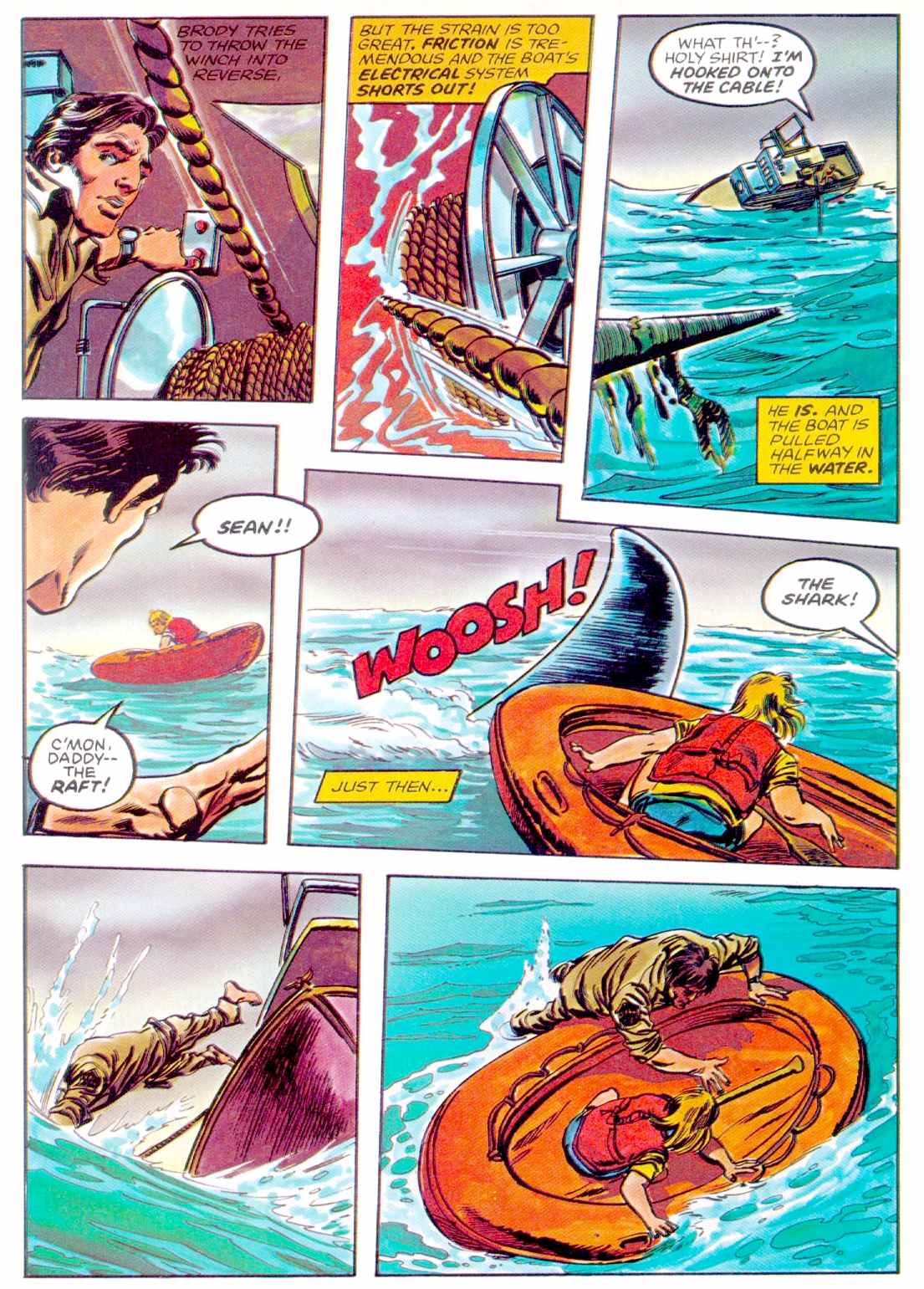

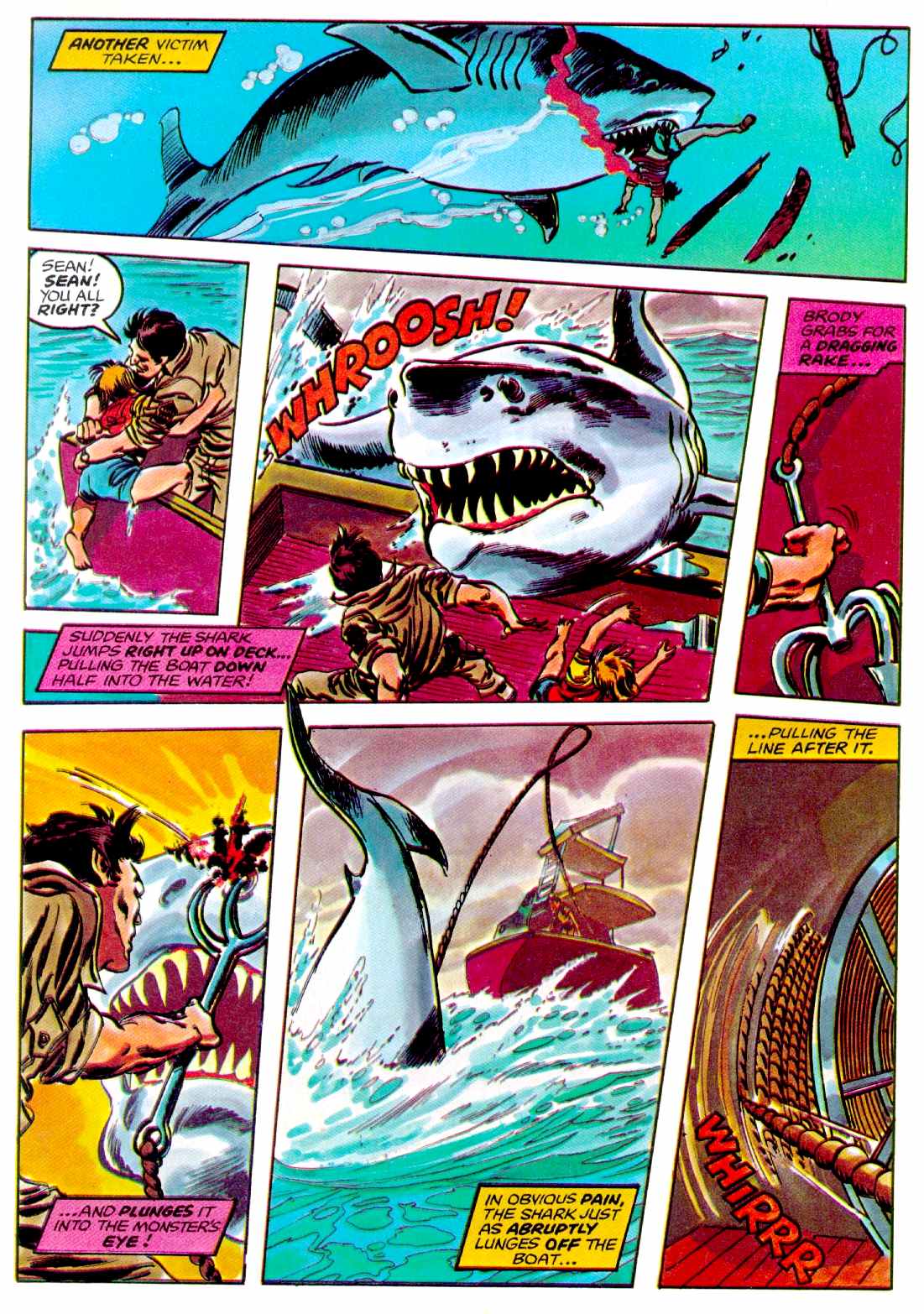

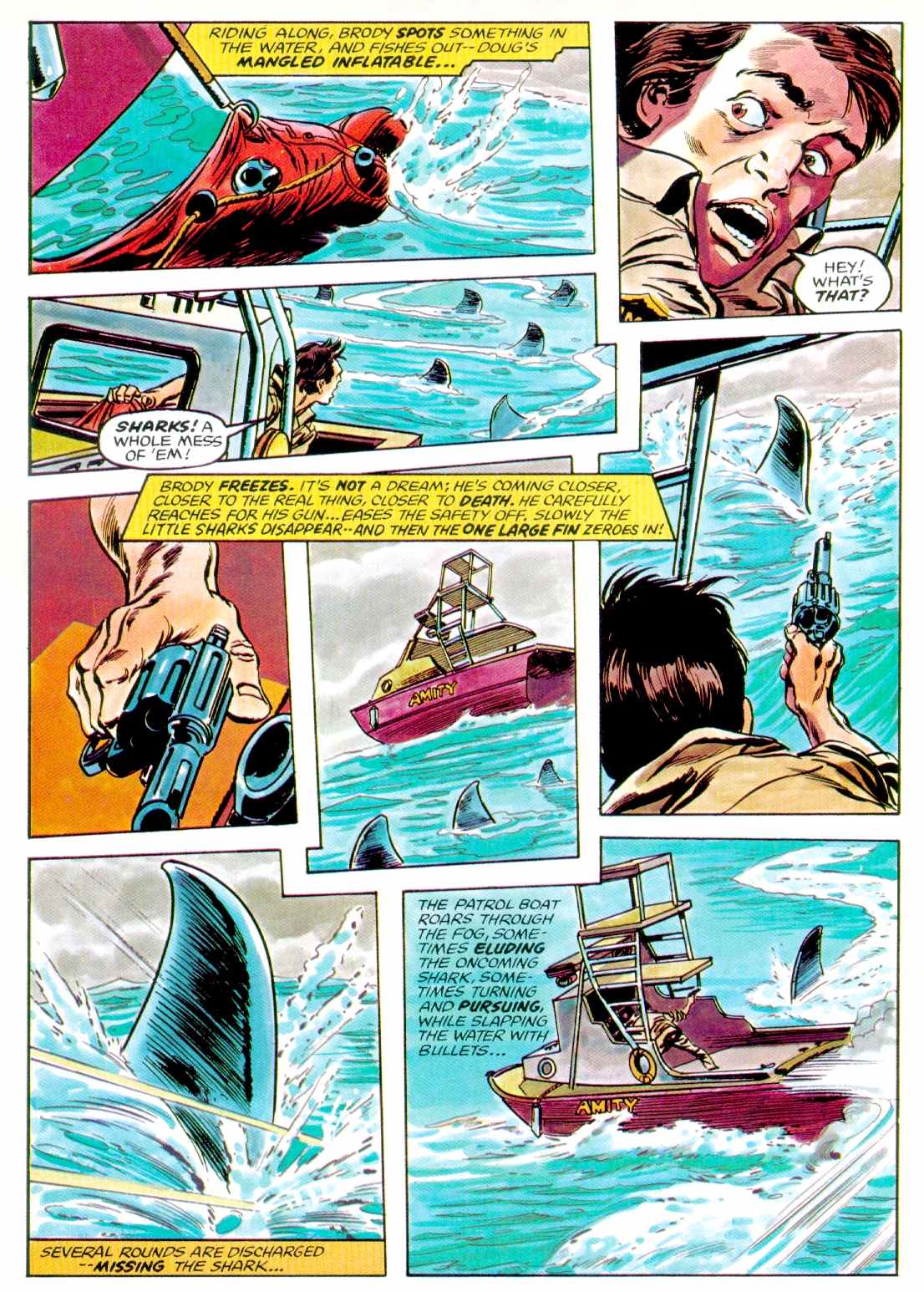

GRAPHIC

NOVEL - JAWS 2 (MARVEL)

Jaws

2 did not have the sound track that thrilled audiences in the movie

theatres in 1975. By comparison the 1978 sequel was pretty lame. But it

did inspire Marvel to produce a graphic novel, where some of the art is

pretty good, much like a story board, except that the imagineers could

draw whatever they liked. They did not have to think of how to film the

shot with actors, or amalgamate real people with CGI.

THE INDEPENDENT 4 SEPTEMBER 2015 - JAWS @ 40 - IS

PETER BENCHLEY'S BOOK A FORGOTTEN MASTERPIECE

It is forty years since a little-known writer named Peter Benchley published a first novel called Jaws. Estimated sales of 20 million books changed Benchley’s life forever, not to mention popular culture as we know it, helped of course by Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster movie released a year later in 1975.

Without Jaws there would be no Shark Week, no ‘Jumping the Shark’, and, proving that not all great ideas produce good results, no Jaws 2, 3-D or The Revenge. Commentators from Fidel Castro to Slavoj Zizek have had their say about Benchley’s great white. It has been a metaphor for dispassionate nature, international Communism, Watergate, the majesty of the ineffable and Fascism. For Peter

Biskind, the shark was a ‘greatly enlarged, marauding penis’. For the more literal Kingsley

Amis, Jaws was about a bloody great shark that could eat you alive.

While next year’s 40 anniversary of Spielberg’s film will doubtless be accompanied by anniversary DVDs and documentaries reiterating the rigours of the shoot (mechanical sharks sinking, Robert Shaw drinking), Benchley’s prose man-eater has entered middle-age rather quietly. His UK publishers have not issued a celebratory edition, although a 40 anniversary Jaws has been released in the

United

States.

Perhaps the nearest thing to a birthday cake is Will Self’s new novel, Shark – although like a recent Radio 4 documentary, he seems more in love with Spielberg’s movie than Benchley’s book. Self centres on the USS Indianapolis scene dreamed up by screen-writers Howard Sackler and Carl Gottlieb, and Robert Shaw who played Quint himself.

The muted celebrations reflect the idea that Benchley’s novel has been swallowed whole by Spielberg’s film. Jaws not only broke box office records, it would not look out of place in any top 50 movie list. Benchley’s original would struggle to make most literary critics’ top 50,000 books. There is little to match Spielberg’s marriage of propulsive storytelling with visual innovation: the dolly zoom on Martin Brody after Alex Kintner is attacked on a

lilo; the camera placed wave-high to enhance the vulnerability of unsuspecting bathers.

Benchley’s prose is by turns functional (‘lacking the flotation bladder common to other fish…it survived only by moving’) and melodramatic to occasionally risible degrees: ‘He screamed, an ejaculation of hopelessness’. His dialogue too lacks the memorable pith of the film script. Sing farewell and adieu to lines like: “You go in the cage. Cage goes in the water. Shark’s in the water,” “This was no boating accident,” and of course “We’re going to need a bigger boat,” improvised on set by actor Roy

Scheider.

And yet, the hushed celebrations do a disservice to a novel that helped refine the modern bestseller and succeeds in its own right as a compelling, if flawed work of popular fiction. Benchley dreamed up that title. We take its strange power for granted now, but it’s an inspired choice, even more so when one considers the terrible alternatives the author entertained. Many are pretentious: A Question of Evil, Anthropophagus, Jaws of Despair, Dark White. Some are baffling:

Squam, Letter on Mundus, Pices Redux. Some are simply terrible: Omnivore, The Edge of Gloom and What Have We Done? Jaws – plural – possesses a latent, biting power that intrigued Stephen Spielberg, although he initially thought was it about a pornographic dentist.

Benchley also invented many of the film’s most memorable set-pieces: the killing of Alex

Kintner, his grieving mother’s confrontation with Martin Brody, and the opening, at once mysterious and shocking, primeval and terrifying. Benchley created Amity, a town whose very existence is threatened by the shark’s taste for tourists, and the political pressures heaped on Police Chief Martin Brody.

In a sense, Benchley was simply writing what he knew. Born in New York City, he spent his summers sailing and

swimming the waters off Nantucket. His father, Nathaniel, was a respected children’s novelist. His grandfather, Robert, was the revered Algonquin wit. Having cut his teeth writing speeches for President Lyndon Johnson, Benchley became a freelance writer, hoarding two ideas for lunches with New York literary editors: a non-fiction book about pirates, and a novel about a 4,500 pound great white shark attacking swimmers off Long Island. Eventually Tom Congdon at Doubleday bit, paying $1000 for four chapters, which Benchley wrote funny to Congdon’s distaste. The jokes were removed, and the rest was history, eventually.

Jaws was an instant hit, although not a bona fide phenomenon until its paperback release timed to coincide with the movie. The hardback was actually kept from number one by Richard Adams’ Watership Down – offering the pleasing image of a 20-foot great white being fought off by several cute bunny rabbits.

Read today, the novel’s fascination is often inextricable from its weakness. Benchley threw everything at his debut, including a vague mafia plot surrounding the town’s mayor Larry Vaughan, which owes more to Mario Puzo’s The Godfather than Benchley’s familiarity with the Cosa Nostra.

There are doses of un-Spielbergian sex, which are dated to the point of offensiveness: Ellen Brody’s rape

fantasises, for example. Nevertheless, her brief affair with Matt Hooper gives the character depths that are absent in the movie where Mrs Brody is little more than a worried wife and mother. She is this in the novel too, but with a job, a hinterland, desires, regrets and something approaching three dimensions.

Benchley’s characters are singularly unlikeable, and all the more interesting for it. Brody remains the focal point, but is edgier, with class and sexual chips on his shoulder. Many are placed there by Matt Hooper, younger, hunkier and

WASP-ier than Richard Dreyfuss’ witty ichthyologist. Quint, however, is essentially

Quint, a Captain Ahab for the 1970s: two-legged admittedly, but still mad, bad and dangerous to know.

This depiction of human frailty hints at Benchley’s main triumph over Spielberg: namely, the portrayal of the shark at the end of the story. In the film, Quint’s laconic rage while recalling his survival of the USS Indianapolis transforms Jaws into a revenge tragedy. Relentless, remorseless and even devious, the shark is a smiling villain, more Lee Van Cleef than

Moby

Dick. The Western subtext breaks the surface in the final showdown between great white and Sheriff Martin Brody. The joyful climax, enhanced by Matt Hooper’s resurrection, offers little doubt who we should be rooting for.

The respective conclusions were bones of contention for Benchley and Spielberg. Benchley thought the movie’s was absurd. Spielberg countered, not without cause: “If I’ve got them for two hours, the audience will believe whatever I do in the last three minutes.” His high-octane finale addressed a problem of his own: that the novel ends on a ‘downer’. Benchley’s shark simply stops swimming, defeated by days of punishment and literally choking on

Quint: ‘It seemed to fall away, an apparition evanescing into darkness.’ This downbeat conclusion makes a more upscale argument than the film is capable of. Benchley’s shark is an amoral force of nature: not bad, just hungry. And what amoral nature has unleashed, so amoral nature reclaims in death. As Brody swims home, the inference lingers that Amity, not the ocean, is home to genuine evil: corruption, selfishness, infidelity, lies, fury and greed.

Benchley, who died in 2006, would repent his depiction of the great white shark, which now exists on the endangered species list. The great whites killed by accident and design are just a fraction of the 100 million sharks killed each year, largely for their fins. Warnings about the real villains of this tragedy – human beings – are present in Peter Benchley’s Jaws, not Steven Spielberg’s. One day we might even read it and weep.

By James Kidd

WHAT

THE PAPERS SAID

Film critics were a

more skeptical of the film’s true worth. This is how five major critics reviewed Jaws after its

release:

1. “Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is a sensationally effective action picture, a scary thriller that works all the better because it’s populated with characters that have been developed into human beings we get to know and care about. It’s a film that’s as frightening as The Exorcist, and yet it’s a nicer kind of fright, somehow more fun because we’re being scared by an outdoor-adventure saga instead of by a brimstone-and-vomit devil.” —

Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

2. “If you think about Jaws for more than 45 seconds you will recognize it as nonsense, but it’s the sort of nonsense that can be a good deal of fun, if you like to have the wits scared out of you at irregular intervals.” — Vincent Canby,

New York Times

3. “So far I’ve managed to avoid describing the story or any of the humans involved in it. That’s because what this movie is about, and where it succeeds best, is the primordial level of fear. The characters, for the most part, and the non-fish elements in the story, are comparatively weak and not believable.”

"When the fear level drops off, for example, you'll begin questioning the realism of how this little town fights the fish that threatens to close its beaches and thereby destroy its summer tourist economy. You'll wonder why they don't ultimately call in the Coast Guard, and you'll wonder, when it comes to killing the

fish, why three men have to risk their necks. Why doesn't somebody just get a big mother of a gun and blow the shark out of the

water?"

— Gene

Siskel, Chicago Tribune

4. “The first and crucial thing to say about the movie Universal has made from Peter Benchley’s bestseller Jaws … is that the PG rating is grievously wrong and misleading. The studio has rightly added its own cautionary notices in the ads, and the fact is that Jaws is too gruesome for children, and likely to turn the stomach of the impressionable at any age.” — Charles

Champlin, Los Angeles Times

5. “It may be the most cheerfully perverse scare movie ever made. Even while you’re convulsed with laughter you’re still apprehensive, because the editing rhythms are very tricky, and the shock images loom up huge, right on top of you. The film belongs to the pulpiest sci-fi monster-movie tradition, yet it stands some of the old conventions on their head. Though Jaws has more zest than an early Woody Allen picture, and a lot more

electricity, it’s funny in a Woody Allen way. —

Pauline

Kael, The New Yorker

THE GUARDIAN 31 MAY 2015 - JAWS, 40 YEARS ON - ONE OF THE GREAT AMERICAN CINEMA CLASSICS

The true meaning of Jaws has been picked over by critics and academics ever since its release in June 1975, and even its status as the first summer blockbuster has been questioned. But isn’t it just about a killer shark?

First things first; Jaws is not about a shark. It may have a shark in it – and indeed all over the poster, the soundtrack album, the paperback jacket and so on. It may have scared a generation of cinemagoers out of the water for fear of being bitten in half by the “teeth of the sea”. But the underlying story of Jaws is more complex than the simple terror of being eaten by a very big fish. As a novel, it reads like a morality tale about the dangers of extramarital sex and the inability of a weak father to control his family and his community. As a film, it has been variously interpreted as everything from a depiction of masculinity in crisis to a post-Watergate paranoid parable about corrupt authority figures. But as a cultural phenomenon, the real story of Jaws is how a B-movie-style creature-feature became a genre-defining blockbuster that changed the face of modern cinema. In the wake of the epochal opening of Jaws 40 years ago, the film industry would find itself on the brink of a brave new world wherein saturation marketing and mall-rat teen audiences were the keys to untold riches. To this day, many consider the template of contemporary blockbuster releases to have been laid down in the summer of 1975 by a movie that redefined the parameters of a “hit” – artistically, demographically, financially.

According to David Brown, one of the film’s producers: “Almost everyone remembers when they first saw Jaws. They say, I remember the theatre I was in, I remember what I did when I went home – I wouldn’t even draw the bathwater.” I was no exception. I first saw the movie at the ABC Turnpike Lane in north London at the age of 12. It was a Sunday afternoon and I’d had to catch two separate buses to get to the cinema. I sat on the right-hand side of the packed auditorium and I remember very clearly finding the opening sequence so alarming that I wasn’t sure I’d be able to get through the rest of the film. As I told director Steven Spielberg several decades later, watching poor Susan Backlinie being dragged violently back and forth by an unseen underwater assailant, screaming blue murder, I genuinely feared that I would lose control of my bodily functions (“I like that!” laughed the director).

The lenient A certificate had meant that I’d been able to see the movie on my own, without an accompanying parent or guardian, merely the warning that “the film may be unsuitable for young children”. But the entire cinema seemed utterly traumatised by that unforgettable opening sequence, and in the wake of this ruthlessly efficient curtain-raiser (you see nothing, but fear everything), two people hurried to the exit. As they left, I remember whispering to myself in a state of sublime terror: “I am never going swimming again, I am never going swimming again…”

This, of course, had been the reaction of millions of cinemagoers in the US, where Jaws had become a summer movie sensation. In his influential essay, The New Hollywood, film historian Thomas Schatz notes that Jaws “recalibrated the profit potential of the Hollywood hit and redefined its status as a marketable commodity and cultural phenomenon as well”. Significantly, it achieved this success at a time when “most calculated hits were released during the Christmas holidays”. Not so Jaws, which according to David Brown was “deliberately delayed until people were in the water off the summer beach resorts”. Indeed, one of the film’s most memorable tag-lines was “See it before you go swimming!”. Yet it wasn’t just the resorts where Jaws showed its box‑office teeth.

Despite the fact that the summer months had traditionally been slow for cinemas (why go to the movies when the sun is shining?), Spielberg’s brilliantly constructed shocker struck a nerve with young audiences whose natural environment was not the beach but the shopping mall. Between 1965 and 1970, the number of malls in America had grown from 1,500 to 12,500 and Jaws rode high on the growing wave of multiplex cinemas that these urban meccas increasingly housed. Along with confirming “the viability of the summer hit, indicating an adjustment in seasonal release tactics”, Schatz also argues that Jaws struck a chord with a new generation of moviegoers who had “time and spending money and a penchant for wandering suburban shopping malls and for repeated viewings of their favourite films”. It didn’t hurt that these malls were air-conditioned, with the multiplex cinemas they increasingly housed providing a cool alternative to the sweltering summer heat.

In the wake of Jaws’s extraordinary success, film-makers and studios started to see the summer months not as dog days but as prime time, something that had previously only been true for the declining drive-in market. “The summer blockbuster was born on 20 June 1975, when Jaws opened wide,” wrote the Financial Times’s Nigel Andrews, adding: “In the years after Jaws, the entire release calendar changed.”

This change was apparently confirmed two years later by the May 1977 opening of George Lucas’s Star Wars, with its sequels The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi setting new benchmarks for seasonal franchise profitability. In the process, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas became two of the most influential people in Hollywood, the men who, according to popular folklore, had invented the “summer blockbuster”.

Jaws opened across North America on 464 screens amid an unprecedented publicity blitz: $2.5m was spent on promotion, a substantial chunk of which went on TV advertising, still a novelty at that time. Promotional tie-ins, including Jaws-themed ice-creams, were everywhere. I remember being on holiday in the Isle of Man long before the film’s UK opening (it didn’t arrive here until December) and buying the novel, the T-shirt and a garish Jaws pendant, all on the strength of the insane levels of news coverage that the film’s US opening provoked. “Lifeguards were falling asleep at their stations,” remembered the film’s other producer, Richard

Zanuck, “because nobody was going in the water; they were on the beach reading their book”. In the first 38 days of its release, Jaws sold 25m tickets; its rentals in 1975 were a record-breaking $102.5m. When adjusted for inflation, the film’s total worldwide box office is now estimated at close to $2bn.

Such staggering success proved game-changing, establishing the financial merit of the “front-loading” strategy, which used saturation marketing to turn a movie into an event. According to Carl Gottlieb, who shares Jaws’s screenwriting credit with Peter

Benchley: “That notion of selling a picture as an event, as a phenomenon, as a destination, was born with that release.”

Today, received wisdom has it that Jaws essentially redefined the economic models of Hollywood. This change led to some staggering box-office bonanzas, but it has come at a price. “My husband keeps citing this as the movie that changed the way movies are made,” says Jaws actress (and wife of former Universal boss Sid

Sheinberg) Lorraine Gary (Ellen Brody) in the 1997 BBC documentary In the Teeth of Jaws. “It got us to where we are today, which is, if it’s not a hundred-million-dollar movie, it doesn’t get the kind of support it needs from the studio. It was a good thing at the time [but] it’s an awful legacy to now have everyone used to an enormous hit-you-over-the-head television campaign which costs so much money.”

Whether or not Jaws really did change the film industry for ever is one of the subjects to be debated at the Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium at De Montfort University, Leicester, later in June. Here, prominent academics Peter Krämer and Sheldon Hall will go head to head on the still-heated question of whether Jaws was indeed the “first blockbuster” (Hall thinks not), while others debate subjects as esoteric as “masculinity and crisis in Jaws”, “Jaws and eco-feminism” and (most

tantalisingly) “Jaws: the case of the archetypal American villain as queer dissident attacking the

heteronormative”.

Conference convener Ian Hunter says that the purpose of the event is to investigate the movie’s progress from popcorn hit to cinema classic. “The thing about Jaws is that it’s open to so many interpretations,” says Hunter. “It can be about Watergate, or the bomb, or masculinity, or whatever. Some critics have claimed that it marks the point that Hollywood became more interested in archetypes than characters, but it was also the birth of a new kind of family film. I remember seeing it in Plymouth on Boxing Day 1975 and thinking that this was really a film for us, for the generation of The Towering Inferno and Earthquake, offering the kind of thrills that had previously been the domain of X-rated movies. For me, it remains one of the truly great and lasting classics of American cinema, a perfect piece of movie-making.”

Jaws began life as a 1974 novel by Peter Benchley about a seaside resort named Amity that is terrorised by a great white shark. Police chief Martin Brody, played by Roy Scheider in the film, orders the beaches to be closed, but the mayor and local businessmen insist they stay open – with tragic results. Eventually, Brody is forced to take to the sea with professional shark hunter Quint (Robert Shaw) and ichthyologist Matt Hooper (Richard

Dreyfuss) to hunt down the shark and save the town.

Film rights were secured by Zanuck and Brown for $150,000 (plus $25,000 for a first draft of the script) before the novel had been published (the book sold 5.5m copies before the movie opened). After potential director Dick Richards reportedly blew the assignment by repeatedly referring to the shark as “a whale”, the producers turned to rising director Steven Spielberg, who had just finished work on his feature debut, The Sugarland Express, and had made waves with the TV movie Duel, which pitted an emasculated Dennis Weaver against a giant, predatory truck.

“I always thought that Jaws was kind of like an aquatic version of Duel,” Spielberg told me in 2006, when I interviewed him for a BBC Culture Show special on the eve of his 60th birthday. “It was once again about a very large predator, you know, chasing innocent people and consuming them – irrationally. It was an eating machine. At the same time, I think it was also my own fear of the water. I’ve always been afraid of the water, I was never a very good swimmer. And that probably motivated me more than anything else to want to tell that story.”

The production of Jaws proved problematic from the outset. First, there was the screenplay, which was still in flux when principal photography began in May 1974 (Richard Dreyfuss famously declared: “We started without a script, without a cast and without a shark”). Three drafts of the Jaws script were produced by Benchley before playwright Howard Sackler was brought in to do uncredited rewrites. But still things weren’t quite right and 10 days before the shoot Carl Gottlieb was enlisted to work with Spielberg on some dialogue scenes, bringing more warmth and “levity” to the often unlikable characters. Gottlieb would continue to do rewrites throughout the production, often incorporating material improvised in rehearsal by the cast, with added input from John

Milius.

With a projected budget of between $3.5m and $4m, filming got under way at the Massachusetts resort of Martha’s Vineyard. Several residents were cast in minor roles, but a few feathers were ruffled by the prospect of a Hollywood production rolling into town. “Martha’s Vineyard is a very upmarket place,” says Nick Jones, producer/director of In the Teeth of Jaws. “There is a somewhat snobby element of the super-rich, but the businesses rely on tourist dollars. So there was a little tension between those who wanted the film crew there and those who didn’t. For example, when the production needed to build Quint’s shack on a vacant harbour lot, they were refused planning permission even though it was only a set. Finally, they were allowed to continue on the proviso that they put everything back exactly the way it was, including the trash!”

Nowadays, Martha’s Vineyard attracts a steady stream of tourists eager to visit the locations where Jaws was filmed. “It really is like walking around a movie set,” says Jones. “Before Jaws, there was a certain notoriety from the Ted Kennedy Chappaquiddick scandal, but the movie really eclipsed that. When we were making the documentary, we went with Lee Fierro [the Martha’s Vineyard resident who plays Mrs Kintner in the movie] to the stretch of coast where the beach scenes for Jaws were filmed. It’s very exciting to see those vistas that have become so iconic. And we got taken out to the wreck of the Orca

[Quint’s boat], which was just a shell sticking out of the edge of the water. It was bizarre; we stood in it and touched it – it was like touching a piece of the true cross.”

The Jaws shoot was originally scheduled for 55 days, but the production swiftly turned into a logistical nightmare when the mechanical shark (three full-size, pneumatically animated models were constructed) consistently failed to play ball. Nicknamed Bruce after Spielberg’s lawyer, Bruce Ramer, the shark had been built by Bob

Mattey, who had created the giant squid for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. The models worked fine in the warehouse, but the minute they were dumped into seawater, they started to malfunction. Day after day went by without any usable footage being shot, storms and seasickness the film-makers’ only reward.

Recalling the ordeal of the shoot, Spielberg told me: “Jaws to me was a near-death experience – and a ‘career death’ experience! I went to a party on Martha’s Vineyard and a very well-known actress came over to me and said, ‘I just came back from LA and everybody says this picture is a complete stinker. It’s a total failure and nobody will ever hire you again because you’re profligate in your spending and you’re irresponsible. Everybody’s calling you irresponsible!’ I had never heard the scuttle before, I didn’t ever hear the noise that was coming from Hollywood about me. So I was halfway through shooting the picture and this person tells me that my movie’s a disaster, and I am a disaster, and it’s over. And I really believed for the second half of the film that this was the last time I was ever going to shoot a film on 35mm.”

The lengthy shoot took its toll on the cast too. In particular, tensions emerged between Dreyfuss and Shaw to match those between their respective characters, ichthyologist Matt Hooper and crusty shark-hunter

Quint. Partly modelled on local character Craig Kingsbury (who has a small role in the movie as the ill-fated Ben Gardner), Quint is a hard-drinking troublemaker who takes pleasure in taunting his city boy colleagues. It was a role into which Shaw threw himself with scene-stealing gusto, to the alarm of

Dreyfuss. “There was a kind of sparring that went on between us,” Dreyfuss told the BBC in 1997. “It was both playful and – on my part – desperate. [Shaw] knew how to dish it out so you had to learn how to dish it back. He could be very vicious and his humour could be very cutting.” And, like his character, Shaw enjoyed a drink.

But while Shaw proved a somewhat volatile presence, his work on screen was note-perfect, which was more than could be said for the shark. By the time the film-makers had enough usable footage in the can, the production was more than 100 days over schedule, with the budget spiralling toward the $9m mark, $3m of which had been blown on what Spielberg derisively called “the special defects department”. Yet Bruce’s failure to function proved the making of the film. Unable to get the shark action shots he wanted, Spielberg was forced to take a more Hitchcockian approach, working with editor Verna Fields to conjure tense sequences in which what we don’t see is more important that what we do. Meanwhile, composer John Williams filled in the gaps where the shark should be with an ominous score that has become as synonymous with screen terror as Bernard Herrmann’s themes from Psycho. The result was pure magic, causing Spielberg to concede that “had the shark been working, perhaps the film would have made half the money and been half as scary”.

It wasn’t until Jaws was test-screened at the Medallion theatre, Dallas, in March 1975 that the film-makers got the sense that they were on to a hit. “That was the first time I realised that the shark worked, the movie worked, everything about it worked,” Spielberg told me. “The audience came out of their seats. Popcorn was flying in front of the screen twice during the movie. And then I got greedy and thought, gee, could I make the popcorn fly out of their boxes three times? And that’s when I shot that scene in my editor Verna’s pool. I had this idea that maybe when Richard

[Dreyfuss] goes underwater to dig the tooth out [of the sunken boat], what if Ben Gardner’s entire head comes out of the hole? And so I shot it in her pool with a prosthetic head and a plywood boat.”

The scene of Ben Gardner’s mutilated head floating into view did indeed prove a showstopper. It was just one of a number of intense, gory sequences that earned Jaws the reputation of being the most shocking movie ever to be awarded a family-friendly PG rating in the US. Writing in the Los Angeles Times, critic Charles Champlin complained that “the PG rating is grievously wrong and misleading… Jaws is too gruesome for children and likely to turn the stomach of the impressionable at any age.” (The Motion Picture Association of America defended its lenient rating by pointing out that “nobody ever got mugged by a shark”.)

All of which brings us back to the thorny question of what Jaws is really about. For years, I have insisted that Jaws is a classic monster movie “morality tale” in which the watery fate of potential victims is sealed by their on-land behaviour. Stephen King memorably wrote: “Within the frame of most horror tales we find a moral code so strong it would make a Puritan smile”, and that certainly seems to apply to Jaws. Key to this reading is the character of Hooper, who [plot spoilers ahead!] dies in the novel after having a sordid fling with Brody’s wife, Ellen, but miraculously survives on screen, largely because the affair doesn’t happen in the film.

Benchley, who makes a cameo appearance in the movie as a news reporter, remembers that the very first thing Zanuck told him when writing the script was to lose “that love story, the whole sex nonsense”. Spielberg agreed, confirming to me that “my first impulse was to get rid of the melodrama and the soap opera aspects of the novel, the whole love affair with the ichthyologist and the police chief’s wife”. Instead, he wanted to “go right for that third act”, cutting to the chase with dramatic results. But once the affair had been removed, so too was the subtextual justification for Hooper’s violent death.

Although the official explanation for Hooper surviving the shark-cage attack was the unplanned wrecking of the empty cage by a real-life predator (and stuntman Carl Rizzo’s understandable reluctance to get back in the water), it seemed clear to me that without the infidelity subplot Hooper became a heroic character who had to live. When I interviewed Spielberg in 2006, he reluctantly conceded that there was some logic in this. But by the time I spoke to him again in 2012, for BBC Radio 5 Live, he wasn’t buying it.

“The shark doesn’t care whether you’re married or single,” he laughed. “It just wants to eat

ya!” But what about Hooper’s survival? I insisted. Surely that only makes sense because you cut out the affair? “Well, I cut the soap opera because I wanted to go out and do a sea-hunt movie,” Spielberg demurred. “I wasn’t interested in doing Peyton Place.”

So, Jaws isn’t a film about infidelity? (Or masculinity? Or Watergate? Or whatever?)

“No,” replied Spielberg definitively. “It’s a film about a shark.”

By Mark Kermode (Observer film critic)

OTHER

NOTABLE SHARK

MOVIES

Ever

since Jaws captured the imagination of a public fascinated by sharks,

movie companies and film producers have been putting out variations on a

theme. One of them is more of a documentary about the Indianapolis

sinking, that is adequate, but not exceptional.

Best

movies of 1975 HD Youtube

TOP

FILMS IN 1975

1.

Jaws

- The original shark attack thriller (Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw)

2.

One

Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (Jack Nicholson)

3.

Three

Days of the Condor (Robert Redford)

4.

The

Return of the Pink Panther (Peter Sellers)

5.

Monty

Python and the Holy Grail (Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, John Cleese)

6.

The

Rocky Horror Picture Show (Tim Curry)

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/may/31/jaws-40-years-on-truly-great-lasting-classics-of-america-cinema

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/jaws-40-peter-benchley-s-book-forgotten-masterpiece-9711459.html

https://www.boxofficemojo.com/

|